Melissa Errico and Charlotte Moore in Conversation

August 1st, 2018

Tony Award nominee Melissa Errico was one of the very first people I ever interviewed, back when I headed up the theatre section of my high school newspaper (in other words, I was the only person who cared to write about theatre). After seeing Melissa in a Broadway show one rainy night, I approached her at the stage door hoping to ask her a few questions. She did me one better, telling me to email her, then encouraging me to come to more of her shows and ask her more questions. We’ve kept in touch ever since. I even worked as her assistant one summer, and have helped her prep for several concerts and cabarets. Needless to say, I was thrilled when the opportunity arose this summer to speak with Melissa and her mentor Charlotte Moore in a piece for The Interval.

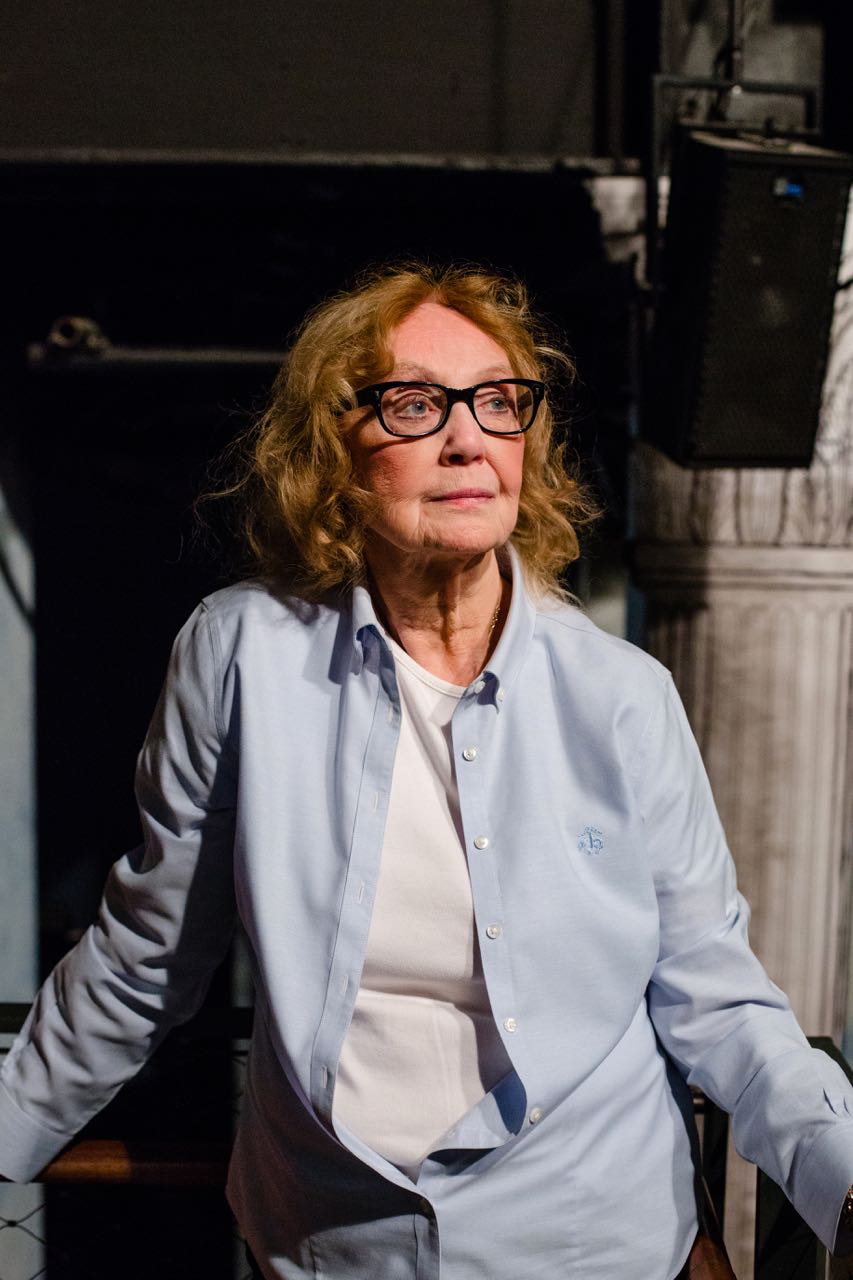

Charlotte Moore, a Tony Award nominee and Obie Award winner with numerous Broadway credits, co-founded her own theatre company back in the late 1980s. It has since become the award-winning Irish Repertory Theatre, of which Charlotte is the Artistic Director. Charlotte has literally built this theatre from the ground up, doing everything from scrubbing the toilets to directing movie stars in critically-acclaimed productions. Currently, she is directing a new adaptation of the 1965 Alan Jay Lerner and Burton Lane musical On a Clear Day You Can See Forever, starring Melissa, who frequently works with Charlotte at the Irish Rep.

The basis of this quirky—perhaps seemingly insane—show centers around concepts such as ESP, past life regression, and reincarnation, which are still very much on certain celebrities’ minds today. Charlotte’s new version of Clear Day sticks to the same bizarre premise of protagonist Daisy going to a hypnotist in an attempt to quit her smoking habit. The hypnotist, Dr. Mark Bruckner, is perhaps too successful, regressing Daisy to a past life and falling in love with her 18th-century alter-ego, a radical, ill-fated heiress named Melinda. Daisy herself, meanwhile, starts to fall for Mark, unaware that she is two thirds of a love triangle. Gone from this production is Daisy’s husband Warren, the original impetus for Daisy’s desire to quit smoking. Daisy’s drives and desires in this Clear Day are all her own (Melinda’s notwithstanding).

I recently visited the Irish Rep, on a not-quite-clear summer day, which happened to be Charlotte’s birthday. The inimitable director gave me a tour of the Irish Rep’s newly renovated space, which includes a mainstage theatre and a black box, on West 22nd Street in Chelsea. She and “Meliss” (as Charlotte affectionately calls her) spoke with me about their experiences working together as “two strong women” in the theatre, sharing tales of triumph as well as some of the darker experiences that have informed their takes on the characters in the show and in the theatre industry at large.

This conversation has been edited and condensed.

Charlotte, what motivated you to go from acting on Broadway to founding your own theatre company?

Charlotte: In 1980, I was acting on Broadway [in] Mornings At Seven. Brian Murray, the British actor and director, asked me to do a play Off-Broadway called Summer, by Hugh Leonard. And [also] in that play was Ciarán O’Reilly. Ciarán had come from Ireland. He was an actor. He had been with the Abbey [Theatre]. We liked each other a lot and decided to work together. We decided to do one Irish play: Sean O’Casey’s The Plough and the Stars. It’s a cast of sixteen. Sixteen Irish people. Did I know what I was doing? No. Did I know what I was getting into? No. But I thought, “Oh what fun!” I really did not know what I was doing, but I loved doing it. I also loved being in charge. And so, through making a complete fool of myself, and doing a successful production of that play, I had such a great time that we decided to do another one. That was about 160 [productions] ago, I think. All at once, we found that we were calling ourselves The Irish Repertory Theatre, after two plays. And we just kept doing them. The more plays we kept doing, the more I liked doing them. I’m very, very proud of it. But they stopped asking me to act on Broadway after a while because I was always too busy. Then, to my stunned horror, they said, “She doesn’t act anymore.” And they stopped asking me. But that’s fine, because both Ciarán and I love what we’re doing. We’re very proud of what we’re doing. It’s our 30th anniversary next year.

Congratulations.

Charlotte: Thank you very much. We deserve it.

I was really struck by what you just said about realizing that you liked being in charge, and the awesome, unapologetic confidence with which you said it.

Charlotte: Well, I like being the one who makes the decisions. It’s fun to get to make the decisions, to ask people to do something you think is right, and watch them do it. It’s an amazing experience.

Early on in your career as a director, did you ever have to deal with people in the rehearsal room who tried to question or contradict your authority?

Charlotte: Imagine the first play: sixteen Irish people whom I did not know. Believe me, they knew better than I did. I had no choice; I had to listen to them, which I did. And I did learn from them, and [from] everybody else I’ve ever worked with. I had many years of acting with the best directors working, ever. I always remember what the directors I worked with said, and what worked, and what looked good, and what felt true. I learned from them, and I sucked it all up into my head, and I use it every day of my life. You learn from everybody you work with.

Who were some of the directors that you learned from?

Charlotte: Hal Prince [taught me], don’t ever let anybody tell you no. Don’t ever let anybody tell you, “you can’t do that.” Stephen Porter was a director whom I worshipped. He did classical theatre, and I learned so much from him. Paul Weidner, whom I lost recently, was the head of the Hartford Stage Company and an Off-Broadway producer. I loved him very much, and learned from him. Michael Montel, who’s still working. He is semi-retired. I learned so much from listening and shutting my mouth, and doing as they asked, and seeing that it worked.

It’s interesting that your list of director-mentors happens to be all men. Do you remember ever seeing any women directors at work, and thinking “If she can do this, I can do it, too?”

Charlotte: No. Not that there haven’t been any. I just haven’t had the luck to work with them. I’m sure that would be wonderful. I would give anything to do that.

What about in the Irish theatrical tradition—how were women represented there? Did Irish women contribute to the culture of storytelling and the theatrical heritage?

Charlotte: Lady Gregory is an example of a great, great Irish storyteller woman. But women were truly in charge of putting the food on the table, and taking care of the children, and doing the farming, while the men did the hard labor. It’s certainly changing now, very quickly, and very nicely, too. Women can do both now. I mean, Melissa has three young children and she works every day of her life, singing, and doing concerts, and doing theatre, and being a fantastic mother.

That’s actually a perfect segue because I did want to ask you—and then, I’m going to ask Melissa the same question in reverse—what was your first impression of Melissa? When did you encounter her for the first time?

Charlotte: I had asked Tony Walton, the brilliant designer, to do The Importance of Being Earnest. He assembled the best cast ever. And amongst them was Melissa Errico. I didn’t know her at all. Then, she came in, a ravishing beauty, and she read for him. She was absolutely wonderful. So, she did Earnest. And then she did Candida. And Major Barbara, in which I acted. [It was] the only time I have acted in this theatre. We were both in that, and shared a dressing room.

I know Melissa really looks up to you and respects you. For years, you’d been the one directing her, telling her what to do onstage, and then suddenly you were scene partners in the trenches together. What was that change in rapport like for you?

Charlotte: Melissa has very strong opinions. She’s very centered within herself and knows what she’s about, what looks best, and what to do. But she will listen to me, and she will do as I ask. She will change it if I tell her it’s not working. I think that’s the basis on which we get along, because I wouldn’t have her in a dozen years if she didn’t do that. And she wouldn’t come and work with me if I didn’t do that. It’s a strange mesh, but it works. Two strong females.

Melissa, when do you first recall meeting Charlotte?

Melissa: I don’t remember a day not knowing Charlotte. My life would be unrecognizable without her. She is a role model. A creative woman with a great sense of humor. She continues to be kind to me. She taught me that people can stand by you for a long time. The Irish Rep is probably the only [theatrical] place where I’ve experienced the authenticity of family.

Charlotte: Her children come here, you know.

Melissa: There’s a sense of being allowed to be a full human being here. In some ways, the Irish Rep’s kindness elicits more kindness back. So this feeling of, “We’re doing the best we can,” makes everybody else do the best they can. You certainly don’t leave here tired or beat down. There’s never a disregard here for how you’re doing. There’s a human element. Show business can so quickly turn inhuman. I’ve come running back here with war stories to pull myself back together sometimes, and to restore why I care at all. I continue to leave here mended.

When you approach a character, Melissa, you tend to immerse yourself in research and preparation. How does your creative process fit into the overall culture of this theatre that Charlotte has built?

Melissa: Well, Charlotte actually doesn’t want me to analyze so much. She wants me to trust.

Charlotte: What I do is—and this fits Melissa to a T—is that [during] the read throughs, I hardly say anything ever. I want to see what the instincts bring, and Melissa’s are amazing. They’re so clean, and so true, and so strong that you don’t bother her much.

Melissa It’s empowering for someone to say something like that. So sometimes I’ll experiment past the goal post, and she’ll pull me right back. She doesn’t want me to come at her with a million questions, because not everybody’s interested in analyzing things. It doesn’t behoove the room, so I keep it to myself, and that’s something we’ve come to understand. She knows I’m piled up with all these ideas about where this fits in, and the 1960s, and the history of the occult. I’m all over. I’m reading about past life regression. I don’t bring all this into the room, per se, because I’m a runaway cart sometimes. Charlotte will say, “Come here, Meliss,” and we’ll just go into Charlotte’s office, and have a chat, and a laugh about things.

And together, the two of you have come up with a new, more feminist take on the character of Daisy.

Melissa: Well, Charlotte told me right away that she got rid of Daisy’s husband Warren because she wanted me to have my own agency, as they say these days. She wanted Daisy to take care of her own future. With Daisy, it could be played that the two sides of her are pulled together by [her love interest] Mark Bruckner, when he says something like, “I don’t know if you’ve lived a million years or million lives or just one, I love you.” I have tried to be ahead of the beat on that. I have tried to take the two sides of myself and to unite those before he gets a word in about it.

Charlotte: And you have.

Melissa: Yeah. Don’t quite know how I did it.

Charlotte: I don’t either, but it would drive me crazy if you hadn’t. I’d be at you all the time to do it, but you have done it.

Melissa: I think it’s Daisy’s job in the soul’s journey to try to fix Melinda’s heartbreak, to try to heal that.

Charlotte: And she does.

Melissa: She pulls herself together and makes herself ready to receive love. I think Daisy and Mark are going to be happy.

Speaking of love, you’ve referred to yourself, when preparing for this role and others, as the last romantic. What do you mean by that, Melissa?

Melissa: These days, people are so tough. I play a lot of characters from a more romantic time. Those are the older shows where people aren’t so neurotic and struggling and angry. I think I do allow for a little bit of what some people would consider old-fashioned romance, that instant spark between people, and not having everything be so well researched in terms of love.

Charlotte: I’m a romantic idiot.

Melissa: The Irish are romantic people, you know.

Charlotte: Irish writers pretend to be dark and realistic and unromantic. They’re absolutely the opposite. Yates is a total romantic if you delve in. He was madly in love with this one and that one. And O’Casey, he was made ill, he’d literally throw up if the love of his life looked at another guy. They’re romantics, and I’m one. Melissa’s one.

Melissa: She’s very romantic. Charlotte really believes in love. I can’t really speak on behalf of the tougher Irish plays they do here, but I have done a Wilde play and a couple of Shaw plays here. They were beautiful, idealist plays. I think everything here is like a dance between beauty and ideas. But I don’t think they lose sight of the beauty of things, the beauty of life and a little touch of fantasy, where things are a little better here than they are in the outside world.

There’s certainly a touch of fantasy in Clear Day. One thing that I find fascinating about Daisy is how unaware she seems to be of her own abilities at the beginning of the show—or maybe she’s consciously repressing them?

Charlotte: Well, she says, “I just want to be like everybody else.”

Melissa: This character’s a lot like Charlotte in some ways. A lot of genius bubbles up, but it’s not manipulative and it’s not something that she’s even conscious of. There’s something about her life energy, her life force, which is so ebullient, and sort of fertile, if you will. She’s completely ebullient with her talents. She hasn’t put a mirror up to herself, [until] the very end of the show when Daisy has a massive psychic experience where she stops an airplane, and she accepts that about herself. In the beginning, she couldn’t even accept that she knew where keys were, never mind airplanes and saving people’s lives. I think she embraces that miracles happen in life. These are literal miracles that Alan Jay Lerner has given us, but there are others. I lost a child, but then a month later I was pregnant [again]. I was in grief, and then a miracle happened. Big and magical things can happen in life, sometimes. And so, in this musical, we’re playing around with the fun bits of reincarnation and so on, but it becomes a metaphor for all the things in life we can’t explain. All the ways that doors burst open, and new things happen, things we didn’t plan. How are we going to explain everything, right? If you can jump past some of the things that seem loopy about this play, it’s allowing for the unexplained.

Charlotte and I were speaking before about how great it is that she so matter-of-factly says, “I like being in charge.” As women, we’re often taught to pretend to be shy of our own power. You’re somebody who presents yourself as being very aware of your instincts and of knowing who you are. What’s it like to play a character discovering that awareness and learning to embrace herself in that way?

Melissa: I may seem confident, but I had to grow up in the presence of my mom’s tenuous sense of self. So I probably pushed myself along, and probably am still pushing myself along. I also have daughters to empower. So, I’m on that jag. I think I have helped move our family forward. Everybody was limited by men and just didn’t have a ton of self-confidence. My grandmother wanted to be a singer, and she got told [by her husband] that she couldn’t be one. My mother used to cry anytime I asked her why she married dad. Not because they weren’t well-suited, but because their generation didn’t define everything overtly, didn’t ask questions like we do. It was hard in that generation. I hope for all of us that we’re going towards a clearer day. It was hard to see clearly, to use the metaphor of this play.

Why do you think that was? Was it societal expectations?

Melissa: People all need to be seen, to practice being heard. Even in show business. I’m a smart woman with a very hip husband and lots of strong ideas, but I had acclimated to wondering, “Am I sexy enough for Hollywood? Am I attractive to this agent? Am I not getting these parts because I never had those kinds of legs?” A million times along the way, I’ve thought about the reasons why I wasn’t desirable or powerful or important. I got used to it; I got used to this creepy feeling. My [college] teacher attacked me in college. I was doing my senior thesis in art history. He threw all my books on the floor and started kissing me. Good God. I had thought I might go into art history. It was looming as an option, a competitor to my love of theatre and acting. That balloon popped. I was very discouraged by how I was treated by my key mentor. I was told by the school that if I went to the Dean, it would become a lawsuit, and did I want to have this following me, a lawsuit at [my college]? But my best friend Rachel told me to at least tell him how you feel. So I said to him, “That thing that happened the other day upset me.” He said, “Well you come in here with all your blousy blouses.” As if he couldn’t help himself, or that I had somehow provoked him. Now, those “blousy blouses” were peasant blouses that button up. They’re round neck and they are sheer, but I always wore a tank [underneath]. I’d loved that look. As a Renaissance Art major, I always thought it almost put me in the paintings.

Charlotte: How old was this guy?

Melissa: Seventy-six. It was bad. I remember his tongue. It was disgusting. He was really creepy.

Charlotte: And you were what?

Melissa: Twenty-one. I’d already done Les Mis. I was about to do Anna Karenina. It opened like the second school ended, so I was probably in rehearsals. And then, I did My Fair Lady that same season, so I had a lot going on. I think I already had a Broadway credit, and the school said, “You know, if you do have a lawsuit, then this is going to be following you at the beginning of your Broadway career.” My point is that someone like Daisy Gamble is ten times more acclimated to being condescended to. She’s so used to it. She feels so grateful, when she’s awake, that he likes her and this is all going well. Whatever she’s learning about herself, it’s like Eliza [from My Fair Lady] getting lessons. She knows something is improving. She can see there’s a warmth growing between them. Then she realizes that he’s been interested in the facets of her other self. And that hurts. I think any woman, even nowadays, would find that a tough pill to swallow.

We’ve been speaking a lot about Daisy here, and I’d love to discuss Melinda a little bit more as well. Do you see her as a separate character? This is a woman who, on the surface at least, is leading an amazing life in 18th century high society, almost like something right out of Lady Montague’s diaries. Melissa, you are somebody who really throws herself into the time period of the character that you’re portraying.

Melissa: I do. I’m like a wannabe Daniel Day Lewis.

Or a wannabe time traveler?

Melissa: I have my own time travel ideas about where I was and so on. I was weeping through some of the early previews because I realized that Melinda really was awakened by [the character] Edward, and then was betrayed. The grief, the hurt, the betrayal that Melinda has felt [is analogous to] Daisy being dumped so many times. We travel as groups, so Rachel Coloff, the woman who plays Melinda’s mother, is Daisy’s mother too. She tells Melinda something to the effect of, “Get over it. Men are cheats. Put the hurt down,” as my mother used to say when I had problems. I used to want to write about my problems. And my mom used to say to me, “You write them in invisible ink.” She didn’t want me to speak my darkness, to speak what I was feeling, the things you would want to say in a diary, the things you would want to say in a strong letter. “Write them in invisible ink,” she used to advise.

Well, you no longer seem to be writing in invisible ink. In addition to being a performer, you’re also a published author. In fact, you recently wrote an article for The New York Times in which you suggest that we can still learn a lot from problematic heroines in older musicals, like Lerner’s My Fair Lady, Camelot, and Clear Day. Are you endeavoring to update the narrative, compensate for it, or expose the original author’s true intention?

Melissa: I could answer that question for hours. My general hope is a combination of all the things you said. I want to keep these shows alive by peeling away every layer I can, without losing sight of the romance and playfulness and mischief built in to the mid-century era musical. It’s a case-by-case thing. Patients don’t all get the same medicine, and honestly not all are fully curable. Source material like Pygmalion and The Once and Future King can hold lots of clues as to who these women actually were, before [the plays] were musicalized—a process that can trim away layers, due to the economy of musicals.

All of the shows mentioned above have scores by male songwriters. Have you found that there is often more inherent agency in a female character in a musical written by a woman?

Melissa: Yes! I adored being a part of the world premiere of Bull Durham. The role of Annie may very well seem like a strange icon for feminism, but I fully saw her in that light. Knowing who [songwriter] Susan Werner is, how smart and grounded she is, it’s impossible to see even that baseball-based plot as anything shy of a great parable led by a sexually confident heroine. But on my mind most these days is Georgia Stitt. I had the privilege of hearing her play songs from her new musical Snow Child in her living room. From the first notes she played for me, I wept. I don’t remember ever being so moved by a piece of music as I was by Georgia’s opening song to that show. There’s something indescribable about feeling a woman’s emotions penned by a woman composer of her degree of inspiration.

Sitting here, I’m very aware of how I’ve looked to you as a mentor, Melissa, and you’ve looked to Charlotte as a mentor. Melissa, you’ve always been very encouraging of intelligence, very adamant that being smart is cool. That was something I really took with me, because not everyone tells teenage girls that it’s cool to be smart.

Melissa: It is cool to be smart. I am just going to stand by that.

Charlotte: And her children. Talk about a role model. She is one for them.

What role do you think female mentorship can play in the theatre industry?

Melissa: I feel like we should start to see each other as all bound by a series of invisible wires and each one should pull all the way back to everyone’s personal history, all the way to your dreams. This sounds like a Mummenschanz image or something. We have to make sure that all the spirits of women stay connected as a network, like a series of these invisible wires.

Charlotte: For a long time, we didn’t take care of one another. A long time.

Melissa: Yeah. We have to.

Charlotte: The light began to shine, and by God, we took it, and ate it, and went with it.