The Gaze of María Irene Fornés: Michelle Memran on Her Documentary “The Rest I Make Up”

Written by Victoria Myers

Photography by Jessica Nash

Photographs courtesy of Michelle Memran

February 13th, 20018

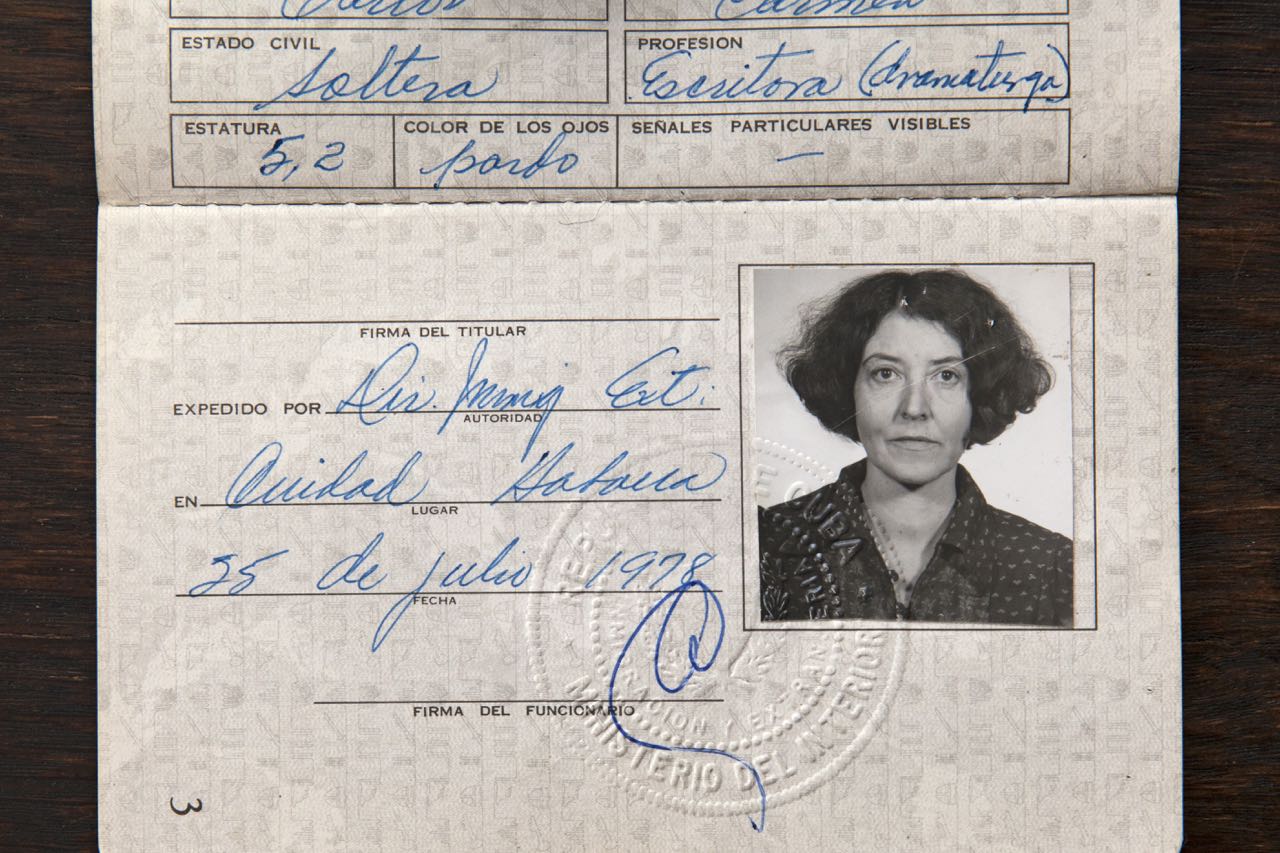

On February 16th, The Rest I Make Up, a documentary about the playwright María Irene Fornés will have its premiere at the Museum of Modern Art’s Doc Fortnight Festival. It’s the first documentary about Fornés, a playwright who was instrumental in forming Off-Off-Broadway theatre and America’s avant-garde theatre movement. And who, like many women who broke ground, has not gotten the same public recognition as the men who were in her orbit. But her influence has remained alive through her work and the young people who frequently read it in college. One such young person was the director of The Rest I Make Up, Michelle Memran. After a meeting in the late 90s when Michelle was in her 20s, a friendship between the two began that led them to start making the film, which uses footage over their more than a decade working together. We recently spoke with Michelle, who was occasionally joined by Katie Pearl, a producer on the film, about the process of making the film, her relationship with Fornés, and the playwright’s legacy.

How did your interest in María Irene Fornés begin?

In college, I was taking a playwriting class—I was a journalism major—and we read one of her plays, The Conduct of Life. It was unlike any other play I’ve ever read, and it just blew me away. So I started reading all of her plays then. After college, I started writing about theatre, and ended up pitching a piece on the relationship between playwrights and critics, and playwrights retaliating against critics. [In 1999] I called Irene up, completely intimidated by her. I didn’t think she was going to be listed in the phone book, and she was. And she picked up the phone, and she was like, “Oh sure, I’ll meet you for an interview.” So basically my interest in her was because of The Conduct of Life and reading that play in college. I probably would’ve gone into writing about theatre anyway, but reading such a rich play definitely led to it.

What were your impressions of her on the first meeting?

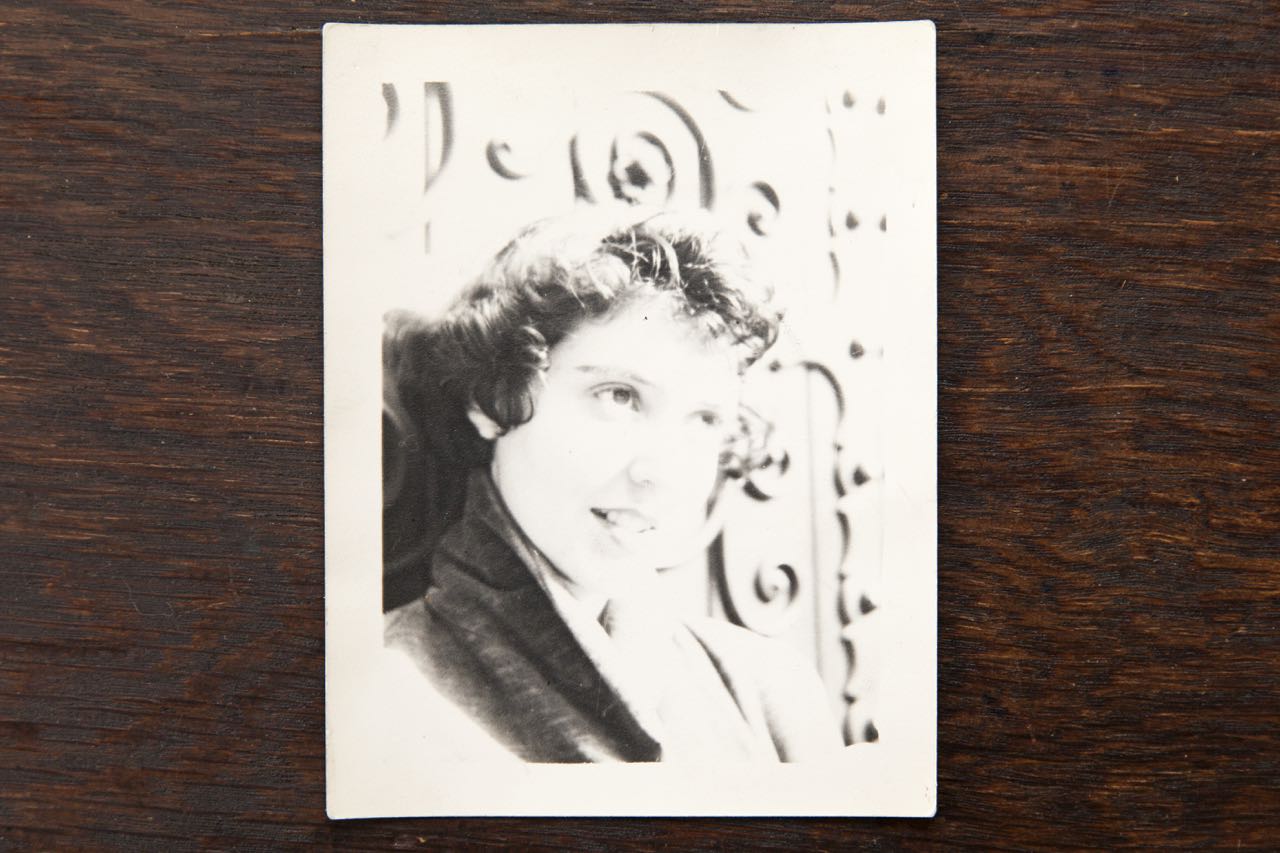

The only impression I had of her up until that point was a photo. It’s the photo that’s used of her on everything. It’s a photo of her when she was probably in her 50s, and looking very formidable and a little scary. So this was the image that I had going in to meet her. We met on the corner of Waverly and 6th, and she looked completely different. She had the gray bob and the red glasses and was entirely open. She was so delighted to meet me. I had heard that she had a disdain for journalists, so I was thrilled that she was thrilled and we sat down at Baluchi’s for a six hours long interview and we didn’t really talk about critics at all because she couldn’t care less. She was just like, “I was just happy to see my name in the paper.” But a friendship was formed that day when we met.

How did you go from that to deciding to make the film?

So we had that lunch. A while later, the article came out—it took me a while, I interviewed like 50 playwrights—but whenever I was in the West Village, I would just call her up and we would go out for lunch, or we’d go to thrift stores, or we’d go to flea markets. She loved going to thrift stores and flea markets. Or just go through Washington Square Park together. And over time, it became clear that she wasn’t writing and she didn’t know why. She wasn’t being asked to teach, and she didn’t know why. And she had all this time for me. Whenever I’d call, she’d be there. So I was like, “This is odd. The woman who’s traveled the world and is incredibly industrious, always working, all of a sudden has all this time.”

And then, one day I was in her apartment. It might have been the first time I actually went into her apartment. I noticed there was mold in the fridge, and there were signs of neglect. They were red flags for me. So I called up her agent, Morgan Jenness, and I said, “I’m a friend of Irene’s and I’m concerned that she might have some form of dementia or something going on with her. And do you know if this is true and who’s taking care of her,” and all this stuff. So Morgan said, “We believe this is the case. Irene won’t go to a doctor, but we’ve been trying to get the community to rally around her.” I started showing up with food and just coming on my lunch breaks and hanging out. It was so much fun to be with her.

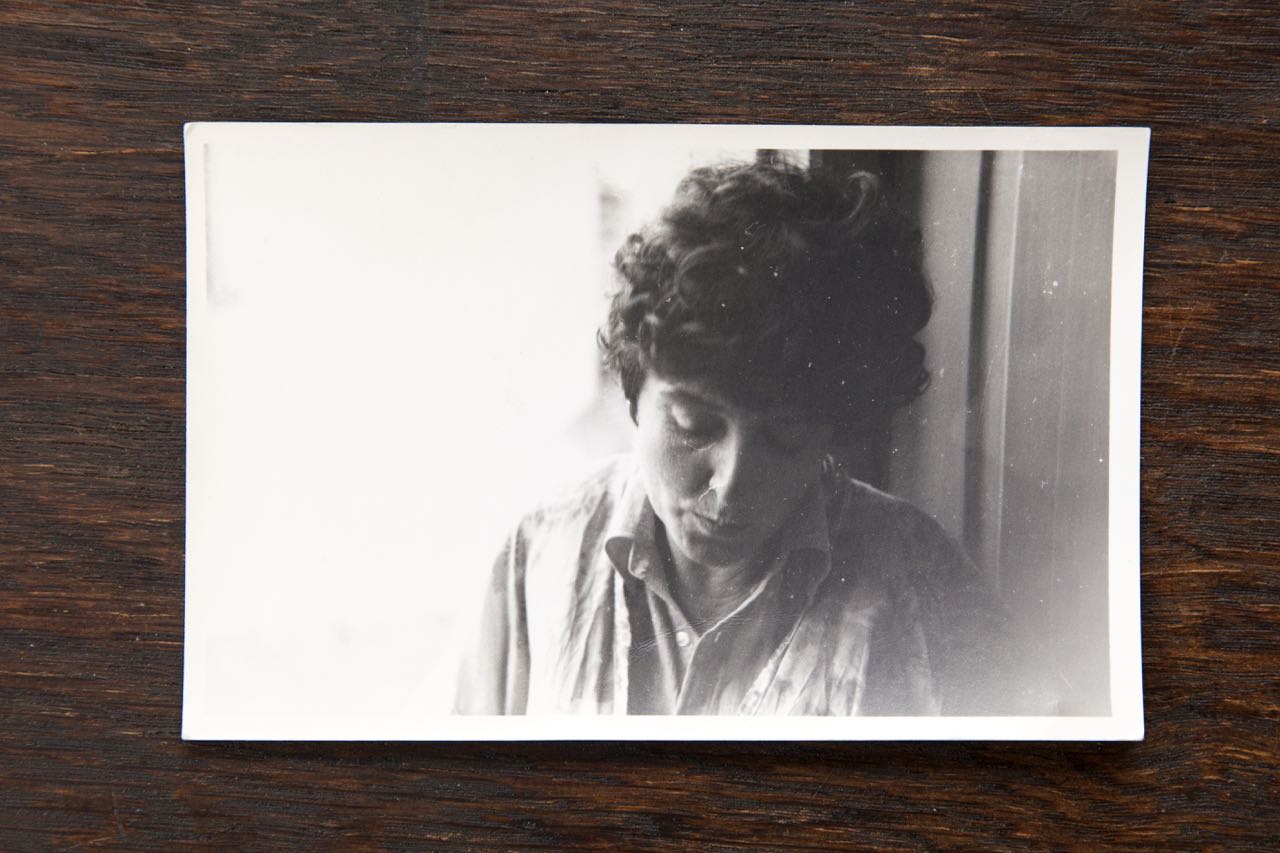

Then one day, we went to Brighton Beach, and I had this old High 8 camera that my dad had gotten me. I had never actually used it. We were with another playwright, and we were on the beach, and the second we turned it on, Irene just lit up in a way that it was like she was performing the monologue of her life. I said, “Irene, does the camera make you uncomfortable?” And she said something like, “Oh, my darling, the camera to me is my beloved. The one who wants me always. And I give everything I have to a camera.” So I called Morgan back and I was like, “Oh my God, this is an amazing way to keep creating.”

It was also at a time where I was a little lost in my career. I didn’t really know what my career was. And so we both were at a crossroads. I was in my mid-20s and Irene was in her 70s. So Morgan said, “I love it. Whatever kind of project you want to do, just do it.” So I borrowed a better camera, and I would just show up with a camera at her house. It wasn’t like we were making a movie, it was just like we were hanging out with a camera. So that’s how it started. And then I started interviewing people, not necessarily as a way for the film, but more so as a way to say, “Hey, this is what’s happening with Irene, do you want to be involved with the community that’s helping to take care of her?”

At what point did it actually turn into a film that you knew you were going to release to the public, or with that goal in mind?

Several months after we began filming, someone found out about the film and wanted to help us. We got a grant. I basically showed the footage on a little camcorder of Irene and they were like, “Oh my God, that’s so Irene, that’s so Irene.” So we got this grant, and we were trying to decide what to do with it. At the time, it was very clear that she was in decline in New York, and her family from Miami and Cuba were very active in calling, sending letters—her brother from Cuba was writing letters, probably like one a week that she would get.

I just said, “Well, we should take this grant and try to take her home.” She kept talking about Cuba and how much she missed Cuba. So that was the point where I hired a cinematographer, Roberto Guerra, an amazing Peruvian cinematographer who would come with us. He basically worked for nothing—he loved Irene and wanted to be a part of it. I got an assistant who had been to Cuba before several times. So that’s when we were making something other than just the camera on the floor and the mic on her back and me not knowing what I’m doing.

Since it started more as a way of doing something for her and for other people to talk about her without necessarily the end goal being a film, once that changed, did you start to think about some of the footage differently? When you stopped being there just as a friend and started being there as a professional?

I never became a professional so it was never an issue. I was always there as a friend. The quality of the film doesn’t change, our intimacy doesn’t change throughout the whole thing even though I enter [the film]. You see me because we have a cinematographer, someone else taking the film. You see me and Irene together in Cuba for the first time. In the New York sections, you only see Irene, because I’m behind the camera. But that intimacy doesn’t change, because there’s enough of me alone with Irene and the camera in Cuba and then onto Miami and Seattle. Product was never a thing we had in mind ever, which is probably why it took so long for us to actually make it. We weren’t like, “Here’s an outline, this is the story, this is going to be great for the film.” It was like, “We’re following Irene’s lead.” So that was a very different way of constructing something. It was like how she would construct one of her plays, which is different.

Do you feel like the fact that she was a writer was partly what allowed you to work that way? That there was a different understanding of the creative process?

Oh, definitely. I mean, I think she would say that she would go through these periods where she would just write and write and write and write and write, and then she would get into her editing mode and be very strict and be very brutal with herself and cross lines out left and right. And that’s what we did. The whole process when we were filming, Irene was in the discovery mode. We were just shooting and shooting and shooting and shooting. I don’t think I ever had a formal, sit-down interview with Irene. I had sit-down interviews with other people and interviews that ended up in the film with her colleagues or other playwrights and directors. But I never said, “Irene, let’s sit down and have an interview.” I think that’s because of the way she worked. She was like, “We’re just going to keep going until you feel like you’re ready.” And it ended up that I kept going for a really long time.

Do you feel that the way that she worked also affected the process in the sense of thinking of life as something you use for the creative process, or even in terms of the boundaries of who owns the story?

I think there was a real awareness, while we were making the film, of Irene actively participating and knowing that we’re making a film. And also in the edit, of maintaining her dignity, that was very clear: when she stops responding to the camera, that we were going to be done. That the film was over.

[Katie Pearl enters]

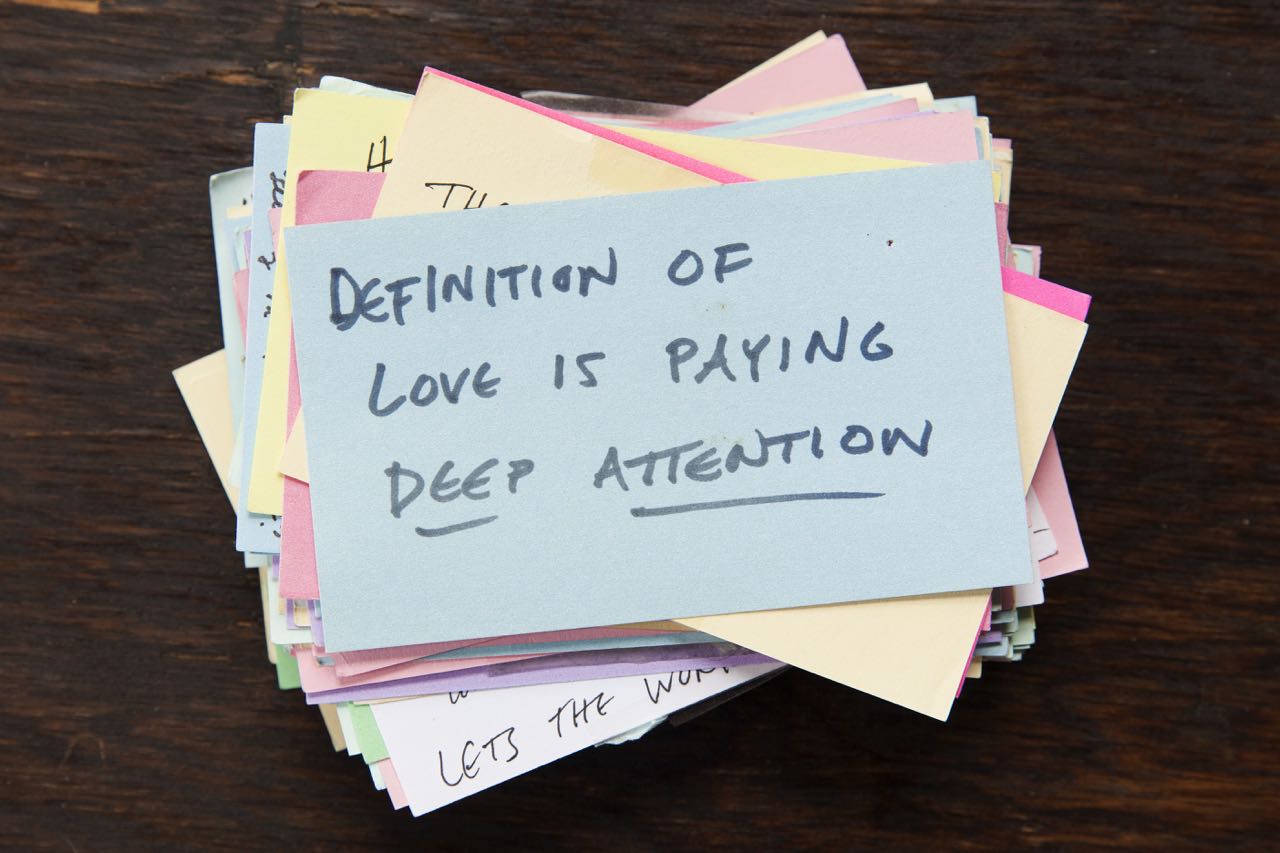

Katie: When Irene writes a play, she follows the lead of the characters, and doesn’t plan. And in the filming process, Michelle often talks about how she follows Irene’s lead, and follows where her memories go, and where her interest goes, and where her delight takes them. Irene wasn’t involved in the editing process, but one thing you talk about discovering is anytime you and Melissa Neidich, who’s the editor, tried to impose something like, “Oh, this’ll be great for the structure of the film,” it never worked. And they had to go back to a completely associative way of continuing to follow Irene’s thoughts. I feel like that’s a really strong parallel between how Irene worked as a writer, and how you learned from her, and then also honored her in the film. The film is so her because of the logic and the methodology that she used in her writing life.

Michelle: And that’s why it’s a film by me and Irene. She’s credited as it being a film by her, as well. Unless we were following where Irene was taking us, we went astray.

There’s that Joan Didion documentary that came out a few months ago that her nephew made, but the film keeps more of a distance and has to navigate those boundaries. But it sounds like you just had a totally different way of working.

Nobody makes documentaries like we made this documentary. This isn’t a biopic. It really has a lot to do with memory and creativity and relationship. Irene is just so compelling to watch as a character. It’s a film about this woman who happens to have dementia, but it’s a side note. The way that it manifests in Irene is this complete ability to be in the present moment. And that’s why I was so drawn to her, because there’s nothing better than hanging out with your favorite playwright and being completely in this five minutes, and then that five minutes, and then the next five minutes. There’s so much in that five minutes that we overlook, but that she didn’t.

Besides how long it took and navigating the structure, what was the most challenging aspect of making the film?

The biggest challenge for me was whether or not I was going to be in it, and how much I was going to be in it. It was such a collaboration that I didn’t want to be in it at first. But we did a bunch of trailers and things where I wasn’t, but then we realized that the heart of the story is this relationship between a mentor and a student, in many ways, because I was also thinking that I wanted to write plays. And so to figure out how and where and when to place me in the story was the biggest challenge. I don’t think I could’ve done it in my 20s or as we were making the film, because I didn’t see it. And then, over the years, things have happened in Irene’s life, and things have happened in my life, and we’re working with an amazing editor who found these great ways to insert me into the narrative. It had to take as long as it took. I realize that now, but at the time I was like, “Why can’t we finish this film? What is going on, am I ever going to finish the film?”

[At the beginning] I see this very young, enchanted, adventurous, lost young woman, and by the end of finishing the film, I see that I’ve become the artist that I wanted to be when I started. I’m a secondary character. I’m there to help you see Irene more clearly, and to help you see that relationships are possible to be formed during the onset of this illness, where many people think that if you can’t form new memories, then you can’t form new relationships. And that’s not the case.

What other ways do you feel like you grew or changed as a person over the course of making the film and your relationship with her?

I changed so much. Irene, it took her several years to write Fefu and Her Friends. She started with scraps and scenes, and then stopped working on it for like seven years so she could produce. So she stopped, started producing other plays, then came back to this play, Fefu, and then it was just like she was pulling scenes out of bags and found this great space and started writing for the space. I feel like that was a similar trajectory when I started the film. In the middle of it, I spent a semester at NYU film school. I thought, “Okay, now that we’re making a film, I should be a filmmaker, and I should know what that is.” What I learned from Irene is the second you label something, you lose it.

I think that what I learned throughout the whole process was that you need to trust in the accidents, and trust that the story will get told if it needs to get told. And I learned to let go a lot. Once I followed Irene’s lead, I was able to see that it didn’t matter that it was taking this long, and it didn’t matter that we didn’t actually know where we were going, but that I had trust that we would get there, somewhere, even if that might not be where we thought we were going to end up.

There’s a moment that is on the cutting room floor. I mentioned my name and Irene said something and I said, “You don’t even know who I am.” And she goes, “I may not know who you are, but I know what you are.” She was like, “You’re an artist.” And we were joking around, but she saw something in me at the time that I didn’t see in myself. Over the process of making this film, I have become an artist in that way. I made something.

When I was reading about Irene, one of the things that I found is that a lot of people think that she didn’t get the credit that she deserved in terms of her contribution to the downtown theatre scene.

Totally.

Why do you think that was?

I don’t have any definitive answer but I certainly have my theories. She never played by the rules—in fact, she said she didn’t even know they existed. She didn’t compromise her vision for the sake of commerce. Many of her plays are not immediately accessible on the first read. She was not writing for a regional theatre world, and a season planned around a subscriber base could make artistic directors hesitant to produce her work, which can be violent, sexual, farcical—and is always fearless. Her plays are not written to please. Her storytelling does not roll out the way regional theatre audiences have been taught to expect. Her work existed on the margins, in terms of mainstream productions, but is still taught in and produced by colleges around the world. People say she is a playwright’s playwright, as most dramatists today know—and revere—her work, and many have actually taken her legendary workshops. Her plays are passed on by her students to their students, and there’s been a recent stream of productions and a revived interest in her work. A 40th-anniversary edition of Fefu and Her Friends was just published by PAJ and American Theatre has done a number of pieces on Irene in the past two years. And then there’s this film, which introduces the world to Irene as a remarkable personality and visionary artist, which we’re hoping will lead to more people reading and producing her plays and making the Fornés name more present in the public eye.

What do you hope this film does for her legacy and what do you hope audiences get out of it?

One of the major points of the film is that it introduces people to her work and to her as a person, and that it can be used as a tool and as a resource for people studying her work and also performing her plays. I think it can function as a master class. But I also think, beyond the theatre, it’s really a film about creativity and that it doesn’t go anywhere. It stays with you. And the hope is that Irene stays with you when you leave the theatre.

If you want to know about Irene Fornés, there’s so little that’s out there, and things that are really erroneous, like the Wikipedia page. This is a real opportunity to have her in the room with you, and to learn about her life. But in a very particular way, because you’re only learning what she’s choosing to tell you, because we’re not inserting anything extra in. I really think as we were making it, as we were finishing the edit, it was very clear that this was for her legacy, and we were making it for people to have an intimate connection with someone that they find as elusive as I did before I first met her on that corner of Waverly and 6th.

[After the interview Michelle sent the following about Irene’s condition today]

Irene currently lives at Amsterdam Nursing Home at 112th Street and Amsterdam Avenue. She is 87 years old and is living with late stage dementia. She has her good days and her bad days, like the rest of us, and we still have our visits, which involve lots of Cuban music and hand holding and reciting parts of the film to her. She rarely speaks anymore but is receptive to touch and music and friendly faces. Visitors are always welcome and encouraged, and I’m happy to meet anyone there who’d like to spend some time with “La Maestra.”