Protesting with Lisa Kron: Dispatches from New York and the Midwest

Written by Victoria Myers

Illustrations by Desiree Nasim

March 30th, 2017

On a not terribly chilly evening in mid-February, two men standing in Times Square dressed as Statues of Liberty—one in the traditional sea foam green, the other in gold lamé—watched as a banner, sporting a drawing of Mickey Mouse and Donald Trump dressed as Donald Duck in the traditional sans-pants outfit, with the phrase “#DisneyLetHimGo” at their feet, made its way up 7th Avenue to the chant of “No fear, No hate, Disney don’t collaborate.” The group of protesters, who had convened at 6pm in Bryant Park and made their way across 42nd Street, were about twenty-five in number and continued on past the Statues of Liberty and up Broadway, until they reached the phosphorescent entrance to the Disney Store between 45th and 46th Street. They stood in a small clump outside the doors and continued chanting and handing out fliers, urging Disney CEO Bob Iger to step down from Trump’s Economic Advisory Council. People stopped to take photos on their phones, while others hurried by, annoyed at another inconvenience slowing them down from getting wherever it was that they were going. A family of American tourists from who-knows-where looked on bemused; a good story to tell when they got home. After ten minutes or so, a group of women came out of the Disney store singing a parody of a song from The Little Mermaid with lyrics about Trump. The rest of the group joined in. The whole thing lasted about 45 minutes.

The protest was planned as part of a group called Resist Trump Tuesdays. The previous week they’d met in Lower Manhattan outside of the Chase Bank headquarters and marched to Goldman Sachs, where there were light-up signs that read “Dump Trump” and “Danger Ahead,” and someone handed out signs with the image of Princess Leia saying “Resist.” I learned about Resist Trump Tuesdays from Lisa Kron’s Facebook page where she had written a post encouraging people to show up to protests and offered Resist Trump Tuesdays as an easy way to get involved. Lisa, like many in the theatre community, took to social media after the election of Donald Trump to express her outrage at the direction the country was headed.

For about three weeks, from the end of January to mid-February, New York City existed in liminal space. People went to protests and people went to Broadway shows. After the White House issued a ban on Muslims (on the same day they excluded the Jews from their Holocaust Remembrance statement), people went in droves to JFK and the Brooklyn Courthouse to protest. The next day, thousands gathered in Battery Park for a “No Ban, No Wall” protest. Uptown, in a sterile convention center, Broadway fans stood in hour-long lines for autograph sessions at BroadwayCon. There were protests at Chuck Schumer’s office, rallies outside of the Stonewall Inn, rallies in Washington Square Park, and rallies in Times Square. On a Sunday afternoon at the beginning of February, Fifth Avenue was quiet, with barricades now permanently lining the street. Outside the Apple Store, which has expanded into the space once occupied by FAO Schwarz, the fountain that once stood just outside the doors where clerks in toy solider uniforms greeted patrons is now empty, and two small children run around on the giant slab of concrete. Down the block, a small pro-Trump rally happens, with an even smaller anti-Trump rally right next to it. People stop and take pictures and watch from across the street. A man with a sign that says “Jesus is the solution” wanders back and forth between them. It doesn’t take long before they all go home.

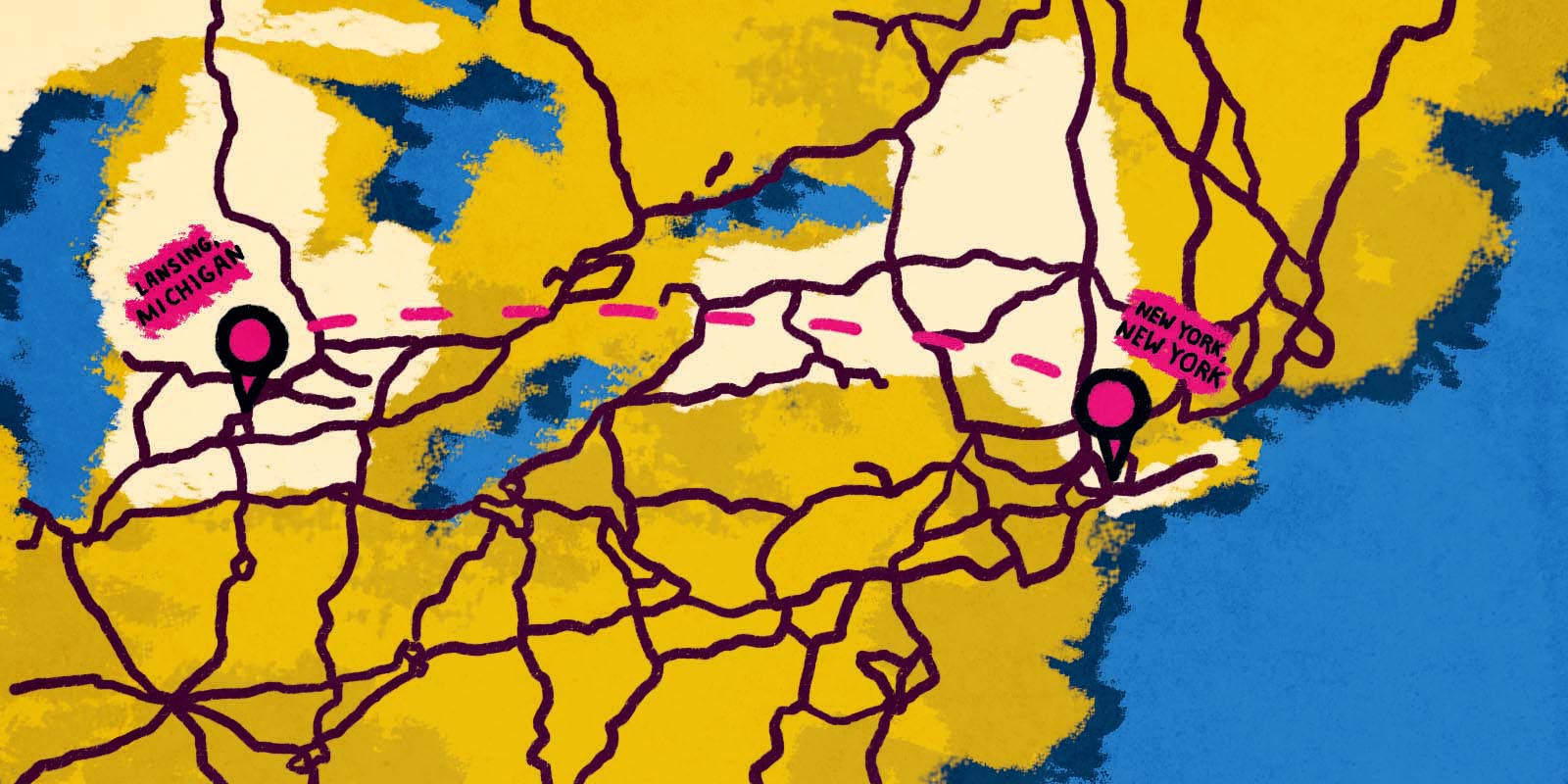

Lisa Kron, who in 2015 won the Tony Award for the history-making Fun Home, was one of the small group of women from the theatre community who showed up at many anti-Trump events. It is perhaps an atavistic response. Her father came to the US at age fifteen, a refugee from the Nazis. He was one of the small number of Jews to receive a US visa; the vast majority were turned down and left to be murdered by the Nazis and their collaborators, including Lisa’s paternal grandparents (though the Nazis lost World War Two, they came dangerously close to having the Holocaust succeed all while the world watched). Lisa was raised in Michigan in a socially engaged family—her mother’s involvement in integrating the Lansing school system became the basis for Lisa’s critically acclaimed play Well. She has recently been flying back and forth between New York and Michigan—a state that went to Trump—where she has been caring for her mother, and has still been finding time to attend protests and organize events in both states.

The other week, after various run-ins and misses with Lisa at protests in New York, I spoke to her on the phone while she was in Michigan about her protesting efforts and impressions.

Let’s start with the Michigan stuff you’ve been doing. You did the ACLU Resistance Training event on Saturday [the 11th]?

I did the ACLU event, and that was really great. Lansing, Michigan, where I grew up, has been a democratic town. Lansing itself is still a democratic town. It’s a union town. Michigan this year went for Trump, and there’s this idea that the coasts are blue and the middle of the country is red. In very broad numbers that’s true, I guess, but it doesn’t reflect the fact that Trump did not win the popular vote, and he wouldn’t have even come as close as he did if it hadn’t been for gerrymandering and voter suppression and things like that.

I’ve been in Michigan a lot. I grew up here and I’ve always been back and forth, but I’ve really been here a lot over the past couple of years, and very intensely over the last couple of months because my mother’s been ill. It’s been very interesting. The resistance movement is very palpable in New York and there’s the assumption that everybody is like-minded, which is true and it’s not true. People are more reserved in the Midwest. It’s not on the surface the way it is in New York, but it’s definitely here.

I went to the ACLU event, and Madeleine [George] and I also went to an Indivisible Lansing meeting. They have four Indivisible Lansing chapters here, and there is a lot going on. And if it’s happening here, it’s happening everywhere. Some of these people are people who’ve always been politically active, and some are people who have not. For the meeting that I went to there were small house parties, and I just chose one that was near where my mom’s condo is, and I didn’t know anybody there. There were a couple of people there who are retired professors—they’re both Mexican-Americans and they’re very active in immigrants’ rights. Then the lady who was throwing the house party, she was involved because she’s got two step-grandchildren, one of whom is a lesbian and the other who is trans. Then another person has an adopted child from China, so suddenly she finds herself in a mixed-race family. That is the way every part of America is. The myth that anywhere it’s just all one thing, it’s just not true.

I looked on the electoral map and Lansing was in a blue county surrounded by a lot of red counties.

That’s correct. It’s been very gerrymandered. The more population density there is, the more Democratic that place becomes. The cities tend to be more Democratic. It’s not entirely true, there are Republican cities here too, but the state has been, historically, a democratic state. A close friend of mine, Erica, her daughter Hadley is going to Wayne State. I have to say, Wayne State sounds to me like a miraculous place. It’s a university that’s in downtown Detroit, and it sounds like it is just a wonderful multicultural mix. Hadley has friends who are Indian and friends who are African-American and friends who are from Africa, and friends who are Pakistani. It’s not a majority white school. Hadley is white, but the school is a real mix, and she’s just having a wonderful time there. That school is, of course, incredibly politically active, so those are young people who are deeply enmeshed in politics. Because of that kind of population, they’re directly affected in so many ways.

It seems like sometimes people in New York can feel a little less useful, because New York is already so Democratic. Do you feel more useful in Michigan?

I do, yeah. I have really liked having my body add to the numbers of people here. After the ACLU meeting, one of the things I suggested was calling up police precincts and talking to them about adopting different policies. There’s a list of policies about their relationship, or separation from, ICE. So the small group that I was in, one of the members is in the process of setting up a meeting with a local police chief. I’m not sure if I’m going to be in town then or not, but if I am, I’m going to certainly go. In New York there are lots of people who go to those things. For that kind of one-on-one interaction, a dozen people can go to a meeting and make a really big difference here. That’s true anywhere, but the ratio of protesters to a target is a little bit different. For the most part the people we’re dealing with in New York are already sort of steeped in those issues. There’s really an opportunity here, I think, to communicate information that has not yet been communicated.

You touched on this before, but do you notice a general atmospheric feeling in terms of how freaked out people are that’s different there than here?

You don’t feel that in the air the way you feel it in New York. In the beginning, right after the election when I was coming here, it really flipped me out. I think when I was talking to people in the beginning, right after the election—and this was a small sample—I think I felt like people were not that freaked out. They didn’t like it, but my experience was that people weren’t as totally flipped out. A friend of mine said to me the other day, “Isn’t Trump so much worse than you thought he was going to be?” I said, “No. He’s exactly as bad as I thought he was going to be.” I think there was a sense of palpable alarm that I felt among my friends and colleagues in New York that I didn’t immediately feel with most people I was interacting with in Michigan. I don’t know the extent to which that is a product of density, and how much it is an actual different cultural metabolism, and how much it’s that people here were just less attuned.

In New York we feel policy more quickly. Our interdependence is something that we are grappling with every single day. The less physically dense a place is, the longer it takes to feel the effects of policies and of, “when this changes, it’s going to have this effect.” You can go for a little while without feeling very interdependent in places outside of New York.

Then also all the stuff that people have been talking about in terms of not normalizing what’s going on, which I’m guessing takes on very different meanings here than in other places.

The policies that are happening now, what Trump is doing, to any vaguely aware person it is unavoidably alarming. People here are alarmed at this point.

There’s also this Martha Gellhorn thing about how Americans, in general, have less of an institutionalized memory of things going horribly wrong. It came about after the Spanish Civil War and World War II, and being upset that Americans wanted to stay out of it. She thought part of American’s lack of sympathy and isolationism came from the fact that most Americans don’t have the memories of having a huge war in this country, or having things go horribly wrong in this country in that way. The idea being that the way Americans process history is just different from people in other places. She was talking about it in a different set of circumstances obviously, but I do wonder if there is some of that going on now. That Americans tend to a-historicize things, and can be detached from history in a way that hasn’t necessarily been allowed in other countries.

I think partly what we’re seeing is different groups who have different relationships to different events in history. African-Americans don’t have to go back anywhere to look for political trauma. It has been playing out since the founding of the country. Their weariness extends, very broadly speaking, to certain kinds of issues and policies and politicians. Charles Blow writes about how the weariness of northern African-Americans is very different from the weariness of southern African-Americans.

I’ve been so heartened to see the response of the Jewish community. I feel like we’ve been trained since we were little. All those exercises, those crazy games that we played in Hebrew school and in our youth groups about, “Here’s the moral choice. How are you going to behave in this moment? Are you going to stand up? Are you going to collaborate with the fascists or are you going to say no?” This mental exercise of picturing ourselves grappling with fascism—I feel like it’s serving Jews very well at this time. I feel like we recognize what’s happening, and we have been extremely alarmed in all the right ways. I’ve been so heartened to see American Jews and American Muslims reaching toward each other in solidarity.

Everybody is responding to their cultural-historical memory and acting based on it. I wouldn’t say there’s one American version of that. I think there are very many versions of that at play right now, which is partly why we see this huge political split. It’s not just what people are watching on the news; it’s also what sort of myths each one of us has metabolized, even about what this country is.

I’ve never been around more Jewish people in my life than at protests these last few months.

I’ve been really very heartened.

Since this isn’t your first rodeo as they say, do you notice a difference between what’s happening now and things you’ve been involved in in the past?

I would say that really I have been activist-adjacent in the past. Like many people, I feel like this has called me to a level of activist engagement that I have not [been at in the past]. My career in the theatre, as a lesbian in the theatre, has been next to a world of activism. I’ve been certainly supportive, and around, and done a lot of benefits, and marched in some marches, but I wouldn’t begin to take credit for doing that kind of work.

I would say, from having had that sort of proximity though, that there is a level of alarm and seriousness right now. Activists can eat each other alive. I feel like right now that kind of chatter—the criticality, the sniping, all those things that can happen [has quieted down]. I feel like we’ve just gotten serious for the moment, and I feel like we’ve just put it aside.

My mother was an activist, so I grew up in rooms where those things were happening. The first days after the election there was, in certain places where people were sort of holding the floor, there was so much mansplaining. There was some mansplaining that I was like, “Oh God, no I can’t. Right now I really can’t take that.” That’s really dropped away. I feel like one of the things that I’ve really appreciated is that people just cede the floor. There’s a sense of, let’s talk a little bit less, and let’s act more. Let’s just do some things rather than talking about them.

Madeleine and I went to see the extraordinary James Baldwin movie [I Am Not Your Negro] at Film Forum in the afternoon, filled as usual with a lot of elderly left-wing Jews, among other people, that I thought, “God, I’ve never heard this audience so quiet.” The level of attention was so high. It wasn’t people doing what I like to call the Jewish pre-complaining, like, “I don’t think I’m going to be able to see.” “I don’t know if it’s loud enough.” “This seat’s going to become uncomfortable in 10 minutes.” None of that. Just quiet. A kind of intensity of attention that I don’t think I’ve ever felt in large groups in this country before.

When we went to the courthouse in Brooklyn the night the first executive order and Muslim ban came out, all these people were gathering. People were at the airports, but then other people gathered at the courthouse to see if there would be an injunction. We were there, and people would be chanting, and then you’d hear through the crowd people say, “Shh, quiet, quiet,” and that whole crowd would get silent. It happened over and over again. Then we’d just stand in silence. Then somebody would say, and other people would repeat, “Press to the front, press to the front.” Then reporters would go to the front. Then people would start to chant again, and they’d go “Shh,” and everybody would get quiet and they would say, “Lawyers coming through, lawyers coming through.”

It was so moving, that level of attention and cooperation, and that feeling of the gravity of the situation. That’s what I feel: a communal sense of gravity that I have never felt. They’re doing this thing, and they’re very clear. Talk about shock and awe; it’s just destruction in every way on every front. It is spinning us around, and it’s traumatizing us, and it’s depleting our emotional resources, our financial resources, our resources in terms of time and attention. It’s also doing this thing, which is to make completely self-evident the thing that we say, which is that attacks on Muslims are the same as attacks on gay people, are the same as attacks on the environment, are the same as attacks on African-Americans, are the same as attacks on women. Every one of these fights, it’s all of our fight, and I think people feel it. We feel it to our bones. We feel each other’s fight with the same gravity that we feel our own. That’s an incredible thing to feel.

I wanted to ask you about a couple of the things you were doing in New York. Because besides the Brooklyn courthouse, I know you also did a couple of the Resist Trump Tuesday things, and I was wondering if you could talk a little bit about a couple of those?

There are so many things happening, and I’m trying to figure out how to focus. I’m doing a terrible job at it, also because I’m going back and forth, and because my mom’s sick, I can’t really focus on anything. I’m just kind of a mess right now in every way. At that time, I had decided that I was going to do two marches a week. I just wanted to be in the street. I do think still that being in the street is very important. We need to see each other. We need to show each other that the intensity of our resistance is not waning. We owe that to each other. We must do it. At that time there were many, many marches all the time. My goal was just to go to two a week, and then to figure out, as we’re all still trying to figure out, how do I coordinate this with my life? How do I not burn myself out? How do I continue to do my work-work? The Resist Trump Tuesdays that I went to in those weeks turned out to be the sort of best march for me to go to. That’s why I did that.

It seems like some of that has kind of calmed down, in the sense that people seem to be going back to normal more than perhaps they were a few weeks ago or a month ago. One of the things that came out of that Masha Gessen piece that everyone was sharing from the New York Review of Books was that it’s a long game. What are your observations about that?

That’s one of the great things about being here. I was having the sense in New York that things were slowing down because people weren’t pouring into the streets every day. In the first few weeks, there would be this call that came out [for a protest], and then you would walk there, and you would see streams of people heading for that place. It was just so exciting. The long game is being played outside of New York. The long game is being played here [in Michigan]. Those town halls that were happening in every state in the country, those sorts of things and those sorts of actions are being worked on all over.

I think that reserve that I felt in Michigan when I first came here, in a way, that was just the first stance in a measured approach. It’s in the middle of the country that we’re going to see the long game being played, and where it must be played, and I feel like it’s being played here. The types of actions that they’re doing are very strategic, they’re very creative. In New York, we were just throwing ourselves into the streets, and that’s emotional, and it did do something, but that is not sustainable. What’s happening here is a different kind of more strategic, sustainable, more thought-out strategy. Right now, the focus is this very small window of time to push back against this disastrous ACA bill. It’s super important because what’s being proposed is monstrous, but also because it will be an important defeat, symbolically.

What do you plan to do next, both in terms of the immediate and in terms of thinking about long-term strategy?

While I’m here, I just like to go to whatever [I can] because I’m interested to see the landscape. I want to meet the people who are working, and I’m interested in seeing what’s happening. In New York also, I’ve gone to a lot of different kinds of meetings, just because I’m interested to see the lay of the land.

I think to be effective you have to focus in more, and I’m not doing a good job of that. I don’t know what I’m doing for the movement at this moment, but I would say that what I have been drawn to do is to show up at a lot of places, and drop in at a lot of different kinds of groups, just because I’m interested to see who’s doing what and what they’re talking about and how they’re operating.

The other thing I’ve been doing is—I’m not much of a social media person, but when I’ve gone to marches, I’ve always taken pictures of myself. I’ve never taken a selfie, I don’t do that, but I do it at the marches because I feel like we have to. It’s a way to keep up the collective energy. Nobody really follows me that much on Twitter, and a little bit more on Instagram, but on Facebook, I have a lot of “friends” on Facebook, and I have felt that it was important to be involved, to go to places, and then to say, “I’m here, come out, please come out.” Michael Chernus, for a while he had a hashtag, #ProtestWithChernus, which I thought was the greatest thing. Who doesn’t want to protest with Chernus? That is just excellent.

The majority of people I know didn’t really go to anything, and I think, for young people especially, it’s good for them to see people actually going and putting actions behind their Facebook statuses.

I understand that reticence. I’m not a person who has done it. A lot of times at marches I’m just like, “Oh my God, that person’s tiresome.” “That’s not that cogent of an idea on that sign.” I’ve been that person. I feel like the urgency of this moment just made me get over myself. Then when you get there, it’s relieving. It’s a terrible time and it’s super stressful and you can just go down a K-hole of fear and despair, and—a million people have said this, and it’s really true—if you take an action, you will feel calmer, and you will feel not so helpless and hopeless. It doesn’t actually take that much to feel less helpless and hopeless. The actions, the small actions, are tremendously powerful, and make a big, big difference, and they make you feel better. They just do.