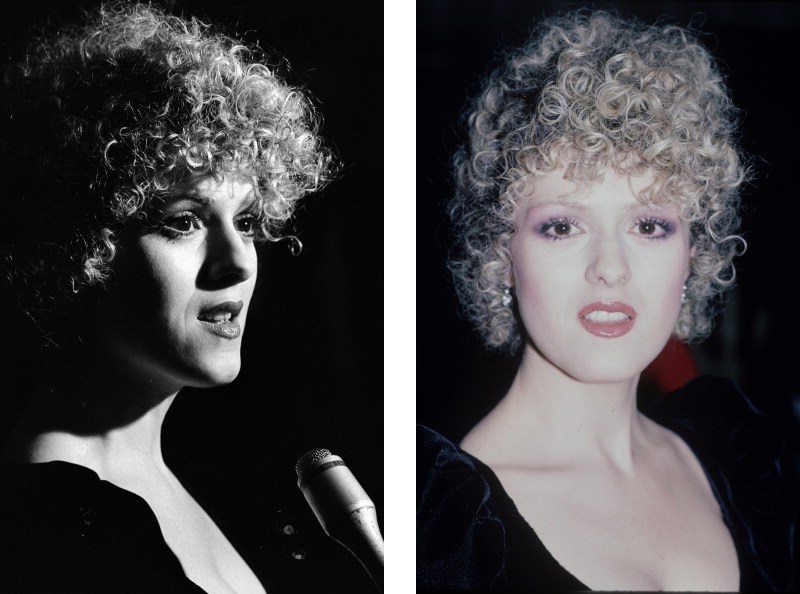

Bernadette Peters: Young and Cute, Forever and Never

Bernadette Peters turns 70 this week. Her name is synonymous with American musical theatre—and the moniker “young and cute forever.” How did that happen? And has she ever really gotten the respect she deserves? We take a romp through 1970s Los Angeles, ’80s New York, and the brain of a ’90s pre-teen to find out how Bernadette Peters became a woman not afraid to take up a lot of space.

February 27th, 2018

In December of 1976, a twenty-eight year old Bernadette Peters sat at a vanity in a pink silk robe with a mass of strawberry blonde hair piled on top of her head. Her body is turned away from the mirror and she stares out beyond the darkness into the firmament. Barely moving, she never bothers to wipe away the tears making a path to the floor. She is singing Stephen Sondheim’s “Send in the Clowns.”

It would be another 34 years before she would perform “Send in the Clowns” in its original context, when at age 62 she would play Desiree Armfeldt in the Broadway revival of A Little Night Music. By 1976, she had already received two Tony nominations, and would go on to receive three more nominations and two wins for Best Leading Actress in a Musical for Song and Dance in 1986 and Annie Get Your Gun in 1999. She’d also appear in a number of television shows and films, winning the Golden Globe for Best Actress in a Musical or Comedy in 1981 for Pennies in Heaven. And in 1995, at age 47, she became the youngest person ever entered into the Theatre Hall of Fame. She had founded a charity, Broadway Barks, to help find homes for animals in shelters. It was during the next two decades that she would acquire the two monikers that would most define her public persona. One: as the premiere interpreter of the work of Stephen Sondheim. Two: as eternally youthful and adorable, perpetually with an air of innocence, a precocious child in the body of 1920s vamp. In early 2005, when Peters was 57 years old, Linda Stasi, writing in The New York Post about a Happy Days reunion show, opened with the following: “With the possible exception of Bernadette Peters, not everyone stays young and cute forever.” It’s a pithy line, and one that encapsulated the box Peters had been put in for her entire adult life, even while being considered the premier interpreter of the work of contemporary musical theatre’s most sophisticated, most lauded, most game-changing composer.

I first discovered Bernadette Peters when I was an 11-year-old who often skipped school to spend my days in my room with the television turned to TVLand. For a brief period in 1996, TVLand would air syndicated episodes of The Sonny & Cher Show. It was my favorite program. This particular episode was the 1976 Christmas special. Sonny and Cher were divorced, and to an 11-year-old who was raised on old movie musicals and I Love Lucy, trying to solve problems by putting on a variety show seemed like a very logical thing to do. For this episode, a man named Captain Kangaroo and a woman named Bernadette Peters were the special guest stars. The two main sketches that Peters appeared in were “Sonny’s Pizza,” where she played a bass drum player who had lost her marching band and then morphed into The Ghost of Pizza Yet to Come in a dream sequence; and as an aspiring actress who is one of four lonely people in a hotel restaurant on Christmas Eve (She had the line, “I guess if I’m going to be a big star, I have to give up some things”). But the most compelling moment of the episode was Peters’ performance of “Send in the Clowns,” which aired with a pre-recorded insert of her dancing around with clowns and singing Cole Porter’s “Be a Clown.” It sounds absurd. It was absurd. It was also wonderful. To me, sitting on my bed in Ohio, she wasn’t just singing, but evoking an entire landscape—the loneliness of success, the toughness needed to survive, the strangeness of being able to observe life and live it, the split between the public and the private self, the end of Sonny and Cher’s marriage, and some other mysterious thing that she did not want anyone to know. I had never seen anything like it. To me, it was so perfect that it was over a year before I figured out that “Send in the Clown” was, in fact, not written expressly for this purpose nor was it written by Sonny and Cher. It made such an impression that two and a half years later, in the spring of 1999 when I was thirteen, I opened my Playbill at the Broadway revival of Annie Get Your Gun, and thought, “Oh, it’s the woman from Sonny and Cher.”

Annie Get Your Gun was Peters’ 11th Broadway show, and the first in six years after the unsuccessful run of The Goodbye Girl. Born in Queens with the name Bernadette Lazzara, and an actress since she was three and a half, Peters first started to gain attention in 1966 with the Off-Off Broadway production of Dames at Sea at Caffe Cino in Greenwich Village. Dames at Sea was billed as a pastiche of 1930s movie musicals, and Peters’ played Ruby, a girl who arrives from the Midwest via bus, and in one day becomes a Broadway star. By 1968, Dames at Sea had expanded into a two-act musical and transferred to the Bouwerie Lane Theatre Off-Broadway. In the interim, Peters made her Off-Broadway debut in The Penny Friend, a musical about a girl who thinks she’s Cinderella, but is actually unconscious and then dies; made her Broadway debut in Johnny No-Trump, a play by Mary Mercier, which closed after one performance, and where she played “a very grown-up 15-year-old;” the Off-Broadway production of Curley McDimple, a spoof of Shirley Temple movies; and on Broadway in George M, which won her a Theatre World Award.

At the time, Peters, barely out of her teens, still lived at home with her parents in Ozone Park in a blue and white bedroom with theatre posters on the walls, that she had shared with her older sister until her sister moved out. She liked jewelry and astrology, and, like most women that age, was still getting over insecurities about her appearance. She liked being alone and later would describe herself as an introvert. She was debating moving into the city and getting her own apartment.

Her parents were traditional, rooted in their Italian heritage, and Catholic (her father used to encourage her to go to church, until he finally gave up since, even though Peters believed in God, she had no interest in organized religion), but her mother had put Bernadette on the path to show business as a small child. She worked some, but never enough to reach the level of child stardom. She was an outgoing but serious child who didn’t like to be told to smile. She wasn’t much interested in childhood and had been in a hurry for it to be over. She later said, “I wouldn’t want to be a child again. When you’re a child, you have thoughts, but nobody listens to you. Nobody has any respect for you.”

In his New York Times review of Dames at Sea, Clive Barnes, who liked the show, declared Bernadette Peters the star and said she was “adorable.” In a profile of her that ran in the Times roughly a month later, she was described as a “kewpie doll” with a mention of her chubby thighs, and the writer, with a wink, called her shape “voluptuous.”

The trend of acknowledging her talent and abilities, but linking them to her physical appearance and describing them through the lens of her adorability and innocence would continue into the next decade and beyond. Her follow up to Dames at Sea was the Broadway adaptation of Fellini’s La Strada, which was supposed to be more play with music than musical, and more Brechtian than classic theatre, but ended up being more failure than success. Peters played Gelsomina, who is sold to a circus performer, falls in love and travels around the country with him. He starts to beat her and, in the end, she dies. During the first rehearsal, the director, Alan Schneider, screened the original film for the entire cast, and the then 21-year-old Peters sat in the back row and laughed when, in the film, Gelsomina’s mother tells her that everything will be fine. She already had ideas about the character. She told The New York Times, “People say Gelsomina’s crazy. She’s not crazy. She’s honest, untouched. She’s people before they start covering up their emotions. She’s pure.” Clive Barnes called the character “a little waif” and Peters “birdlike and croaky,” but that in a better show she would have become a star overnight. He doesn’t elaborate on what made her performance so remarkable other than she looked right and sounded right and the director used her kooky mannerisms and corny modulations well. Barnes also highly praised her for her next show, On the Town, where she played Hildy, whose big number “I Can Cook Too” is a comic semi-seduction, but again, the praise was limited to a description of her as a childlike and enchanting creature. Meanwhile, Walter Kerr found all the women in the show hysterical and interchangeable. The part earned her her first Tony nomination.

In the early 1970s, Peters, who had moved out of her parents’ house and into Manhattan, was already becoming disenchanted with New York and Broadway. Dames at Sea was made into a TV movie, which she’d wanted to do, but got replaced by someone more famous. “You have to remember that if you should get a hit on Broadway, your selling power is still small,” she told After Dark in 1974. She started to do some TV including The Carol Burnett Show. Burnett had seen in her in Dames at Sea, and was so impressed by her comedic abilities that she made her an offer to appear as a guest on her upcoming TV show. For years after, Peters would continually credit Burnett with helping her more than anyone else. The experience with La Strada had been disappointing and she didn’t see the point in “hang[ing] around New York, and do another show that, when I went into it, the music wasn’t as good as it should have been but they said they were going to fix it and they never did, and the script they said they were going to fix and they still haven’t.” She wanted to do work that she could be proud of, even if other people might not like it. She knew people thought she was wrong for On the Town, but she did it anyway. At the opening party Mayor Lindsay tried to look down her dress, and she tried not to notice him doing it. She headed West and did some more TV and a movie where she played a prostitute in 1926, but was still looking at theatre projects, including a new musical by Jerry Herman that was having trouble finding a female lead.

In Mack and Mabel, she played silent film star Mabel Norman, who was influential to the development of the screwball comedy and who died at 37. The musical was troubled, although Peters was reviewed favorably. Again, she would be described as a “little waif” and “wide eyed.” Again, she’d earn a Tony nomination for the role. At 26, it would be her last stage appearance for nearly a decade, and the last of her early career roles where she embodied women who died before they ever got a chance to become old.

By the mid-1970s, Peters had permanently relocated to Los Angeles and spent the formative years of her mid-twenties to almost mid-thirties on the West Coast. Los Angeles in the 70s was, like almost every other remembered place at almost every other remembered time, the best and the worst. It was post-Charles Manson and post-Golden Age. Joan Didion was writing about it. Eve Babitz was writing about it. All in the Family and The Jeffersons were on TV, and so were Happy Days and Little House on the Prairie. Jane Fonda went to Vietnam in 1972 and opened a workout studio in 1979. There were a lot of parties, a lot of drinking, and a lot of drugs. Barbra Streisand’s A Star is Born was released in 1976; Judy Garland had died in 1969.

Peters said she liked living on the West Coast. She had gotten her driver’s license after failing the test twice in the same day, and liked being able to get herself places and liked driving wherever she wanted in her red 1974 Toyota. She worked a lot, but no one knew exactly what to do with her. Not only could she sing and dance, which people kept telling her would limit the way people in Hollywood saw her, but the “in” look for women at the time was tall and rail-thin with long, straight hair, which was another thing people kept telling her, remarking that there was probably a reason why she said “no” to the cake that was always offered at the end of interviews over lunch—and by the way, did she know that she looked like someone from another era and that her speaking voice was unusual? Yes, sure she liked doing period things, and yes, she felt she understood the style, but she also felt like someone who was modern and alive now, since, you know, she actually was; and her voice was her voice, and if people didn’t like it, too bad, what else is there to say; and, I mean, do you really want to talk about cake?

She was described as maybe not quite fitting into the Hollywood scene, since she didn’t smoke and didn’t do drugs and was a vegetarian and didn’t like parties, and definitely didn’t like them if she was asked to perform at them, which she never ever did except for one time, because it was hard to say no after an elderly Groucho Marx had sung. Some people thought she was a little too serious and tried a little too hard and laughed a little too much at her own jokes, which sometimes people thought weren’t funny and/or were too corny, but she found them funny so she told them and laughed at them anyway.

She lived above the Sunset Strip with a miniature poodle named Rocco. She was still interested in astrology and started meditating. Still not a member of an organized religion and still believing in God, she had a spiritual awakening in ’74 that she told The New York Sunday News was “swift, and an awakening to a better life,” and that’s all she cared to share about that. She realized that if she was going to perform, it needed to be about something greater than herself. She told TV Guide in 1976, “To me, an actor is, first and last, somebody with one big responsibility: to lift spirits, to always be this sort of shining light,” and that during Dames at Sea she had “started wondering why I was on stage at all. I thought it was because I loved it. No, I realized I was there to give something to people—to give from the gut.” The TV Guide writer was one of those who thought she laughed too much at her own corny jokes and wondered if she could really play a contemporary, liberal, activist in the new television show All’s Fair.

In 1976 she appeared in two big projects: Mel Brooks’ Silent Movie and All’s Fair from creator Norman Lear, who, when asked if she really looked the part, responded with, “That’s in your eyes, not mine. I saw a skilled comedienne with the range to play probably any style, and period.” Some people thought she was great and some people thought she was too abrasive and came on too strong. The series only lasted one season, but she got a Golden Globe nomination. She also got more attention from the press, which was a challenge for someone who was private and didn’t like to publicly talk about her personal life or her beliefs. She told the writer from The New York Sunday News that she was fairly liberal but, “No—I don’t want to discuss Nixon or Watergate. Something personal happened to me regarding Nixon, and I don’t want to discuss it. Don’t get me wrong, I never met the man.” Honest to God, I have no idea what that means, but I highly suspect that might be exactly the point.

She did more variety shows on television and traveled around with a nightclub act. She was mostly billed as a comic actress: kooky, zany, but still with the innocent waif moniker that had traveled with her from New York, and now with the added of baggage of “girl from another era.” Comedy is, of course, hard, and she was good at it. Her performances were marked with bold, surprising, idiosyncratic choices. Lucille Ball once said about herself that she wasn’t funny, she was brave, and that if the audience was ever even slightly worried that she might get hurt, they wouldn’t laugh. What Lucy knew—and I mean she really knew—is that being a waif, with it’s implied definition of helplessness, and being funny, are mutually exclusive concepts. Peters appeared with Ball and Carol Burnett and Eydie Gorme on The Dinah Shore Show in an episode dedicated to funny women and what it was really like for women in Hollywood. They discussed being taken seriously for their work and not their looks, not being boxed in, sacrifices, being an ambitious woman (while never using the word ambition), and balancing work and family life. Peters, 31 at the time and the only one who had never been married and still not in control of her career, found herself at the receiving end of a lot of advice. Ball, who was approaching 70 and knew better than anybody, seems to be stifling the urge to say what she knew she couldn’t reveal on national television—how hard it really all was and is—that the world never had and never would be calibrated to support the choices of unique, talented, ambitious women. The year was 1979 and Peters was doing her concert act, which would be filmed for TV, and had a starring role in The Jerk with Steve Martin.

Peters met Martin in 1977, and a few months later they began dating. He was, at the time, the most successful stand-up comedian in the country. In early 1982, he’d tell Rolling Stone that what first attracted him to her was that she was independent, that they could talk about show business. Neither of them ever particularly discussed their relationship publically, but they worked together. In 1978, she opened for him at the Riviera in Las Vegas, and he wrote the female lead in The Jerk, his first movie, with her in mind. The Jerk opened to poor reviews but became an enormous success, and is now considered one of the best comedies of all time. They made one other movie together: 1981’s Pennies from Heaven, which exploded the concept of the movie musical. The movie did horribly at the box office, but some critics found it exquisite (it is). Peters won a Golden Globe for her work in the film, and under a different set of circumstances, probably, deservedly, would have gotten an Oscar nomination.

Pennies from Heaven is both thrilling and uncomfortable to watch. The movie is set in the 1930s and uses the popular music from the time to represent what the characters wish they could say and what they wish their lives were like. “Don’t you wish life could be like the songs?” says Arthur, played by Steve Martin. Towards the end of the movie, there is a scene where Arthur and Eileen, played by Peters, go to the movies and dissolve into dancing to “Let’s Face the Music and Dance,” the number made famous by Fred Astaire and Ginger Rogers in Follow the Fleet. In Follow the Fleet the dance is a show-within-a-show number, with no context, without moving the plot forward. In Pennies from Heaven, Martin and Peters dance in an imitation of Fred and Ginger until a chorus of men appear and suddenly their dancing canes grow and grow and grow until they become the bars of a jail cell.

She came back to the New York stage in 1982 in an Off-Broadway play at Manhattan Theatre Club directed by Lynne Meadow and written by Sybille Pearson. In Sally and Marsha she played a South Dakota housewife who has just moved to New York City. It was billed as feminist odd-couple. Her salary was just $210 a week, meaning she was losing money, but she wanted to do the play, and so do the play she did. Frank Rich considered Peters the best thing about the production. In his New York Times review, he said he thought she used her physicality (“big eyes” “kewpie-doll voice”) well, and as an actress was in “top form these days,” finding strength underneath the cuteness. Her part was described as the perfect role for her—“an indomitable waif adrift in the big city.”

New York in the ‘80s was big, big, big and fast, fast, fast. It was the uber-rich, the rise of the yuppie, and starving artists. It was lunch at the Four Seasons. It was the AIDS epidemic. It was Jay McInerney and Bret Easton Ellis and Tama Janowitz. Times Square was still a mess. Everyone was trying to get somewhere, get something. It was the beginning of the end, which is what people always say, and also the beginning of another beginning.

By the start of the ‘80s, Peters had already started to see the holes in the public perception of her, remarking to Esquire in 1982, “There are many different perceptions of me, as far as the public is concerned. I realized recently that people live in different time slots.” She would continue to work in LA and do concerts, but starting in the mid-80s she’d begin another phase in career, the one that would forever establish her as a Broadway star. In the first half of the decade, she released two albums, including one with her painted as a Vargas girl on the cover, had two films out simultaneously (the aforementioned Pennies from Heaven and Heartbeeps), and hosted Saturday Night Live, where she sang song about masturbation. Her mother died in 1982. She broke up with Steve Martin. Writers started to comment that it really was quite difficult to get her to talk about anything personal, although she did start to reveal ambivalence towards the things she was supposed to want versus what she actually wanted. At the beginning of 1982 she was reading Cinderella Complex and told Esquire, “Sometimes I think marriage is what I want, and sometimes I think it’s just a convention.” A few years later, she’d begin to speak about how she was just learning to appreciate and be herself, just learning to be okay with success and ambition and free herself of what she thought all of those things meant. She told The Daily News, “I always had this thing in my mind—when you’re a woman and you’re a success, you’re a ball breaker, you’re terrible. I guess I sold myself this bill of goods, but I’m changing. It’s OK for a woman to be aggressive and successful.” In 1986 she told The New York Post, “I think I equated success with something not good. Losing yourself. Not being a real and good person. Something scared me about it. Then I realized I could be what I want.” “Did this change happen with or before Sunday in the Park with George?,” the writer asked. It was before Sunday. She had lived a life, she wasn’t remade by Stephen Sondheim—if you are looking for a Pygmalion story, you might want to go elsewhere.

In 1983, at the age of 35, she joined a workshop production of a new musical by Stephen Sondheim and James Lapine about Georges Seurat called Sunday in the Park with George. She played Seurat’s model and mistress Dot, and later, in the second act, his daughter. The musical had its Off-Broadway premiere at Playwrights Horizons, and it then moved to Broadway. Peters was reluctant to do the Broadway production since she felt Dot’s journey got lost as the first act progressed. According to Sondheim biographer Meryle Secrest, Sondheim and Lapine originally interpreted this as vanity on her part until they realized that her point was essential to the story. The show would go on to win the Pulitzer Prize for Drama (at the time it was only the sixth musical to ever win the Pulitzer) and Peters got a Tony nomination for her work. In a Daily News interview in conjunction with the Broadway show, she was described as a blend of “sexy siren” and “child who painted herself up in front of mommy’s makeup mirror.” In Frank Rich’s review she’s called “radiant” and “wonderful” and that’s it. It would be Peters who, in the end, would walk away with the title of premiere interpreter of Sondheim’s work.

She won her first Tony Award in 1986 for Andrew Lloyd Webber’s Song and Dance, which opened in the fall of 1985. She told the Chicago Tribune that, to her, Song and Dance, “tells the story of the evolution of a woman. She realizes she shouldn’t live her life by what other people think. She learns she can’t be defined by other people.” Yes, that was something she related to.

She was back in the New York theatre whirl. She was honored by Mayor Koch who said, “No one works harder or makes it look easier or prettier.” Andy Warhol, in his diary, recorded her getting groped by one of his friends at a party thrown by Joseph Papp. She did more film and television, including the film adaption of Tama Janowitz’ Slaves of New York where she said of her role, “People regarded the character as “a victim, but I thought of her as someone unconscious. She seemed to be me eight years ago, someone who didn’t really appreciate herself enough. She was in a fog. She didn’t know her strength.” She would start remarking that she may not be tough, but she was a strong person. She did her second Sondheim show in 1987, where she portrayed The Witch in Into the Woods.

She wouldn’t appear in another Sondheim show for over twenty years, and The Witch in Into the Woods would be the last—and one of only two—Sondheim roles that she would originate. But she started performing his songs in her concerts, and dedicated the entire second act of her 1996 Carnegie Hall debut to his music. The concert was recorded and released as an album, Sondheim, Etc., and a subsequent version of the concert at the Royal Albert Hall in London was filmed and released on DVD. Stephen Holden, in The New York Times, wrote of the Carnegie Hall concert, “The chemistry between the voice of the wise child and the lyrics of Broadway’s ultimate sophisticate filled the hall with a profoundly bittersweet feeling of lessons learned on roads long traveled.” She had worked hard at her job for over three decades and had fought for her accomplishments, and at 46, it all congealed around the same language that had been used to describe her since she was 18. It also ensured her place in Broadway history books.

By 1999, her position as a Broadway star was firmly established, and the her return to the stage at 51 in Annie Get Your Gun was greeted with both excitement and cynicism by people who thought she was wrong for the part and that the source material wouldn’t hold up (the book of the show underwent major changes for the revival). The reviews were not good, although Peters’ performance was praised, even if some continued to think she wasn’t right for the role. Ben Brantley referred to her “oversize little-girl voice” and her “bruisable, fragile quality” that made it hard to believe that she could withstand anything tough or sexual. Brantley thought the lyrics “a doll I can carry” described Peters perfectly. Despite the mixed reviews, people came to see the show for her and she won her second Tony Award.

As a thirteen year old, I knew none of this. All I knew was that Bernadette Peters as Annie Oakley was the best live performance I’d ever seen in my life, ever. In the same way that I’d been so captivated by her performance of “Send in the Clowns” on Sonny and Cher, watching her on stage became a formative experience. It was the first musical that I’d seen where the female lead was the protagonist and not just the woman with the most lines, which still amounted to less than the male lead who was actually the lead. Annie Get Your Gun was her show. I didn’t see anything fragile or doll-like. I saw someone who could be funnier, sing louder, and take up more space than anyone else on stage. Bernadette Peters might be small in size, but to me, she was someone who got to be very, very big in all the ways that mattered.

I begged my mother to let me see the show again, but was only permitted the cast recording and a souvenir program. When I got home from the New York trip, I set about finding out everything I could about Bernadette Peters, keeping articles I’d find in newspapers and magazines in a green, alphabetized accordion folder. I tracked down as many of her movies and cast recordings as I could, including her Sondheim, Etc. CD, along with the DVD of Bernadette Peters in Concert. Sondheim, Etc. became the album that, more than any other, defined my adolescence. It was in my ears on a daily basis and traveled with me around the world. By that time, I had figured out that Sondheim had written “Send in the Clowns,” I knew West Side Story and Gypsy and had seen Forum—and used “Comedy Tonight” as the opening number for mine and my friend’s third grade masterpiece, O.J. Simpson Trial: The Musical!—but almost all of his songs on her album were new to me. I didn’t know their contexts, the characters who sang them, or what had supposedly happened the moment before. All I knew was what I heard Bernadette Peters singing about and the stories I made up in my head to go with them—in other words, the window through which I looked out and saw the world of the song belonged to her, not to him. And her performances of the songs were layered and urgent. She packed the expansiveness of a novel into a three-minute song. It didn’t occur to me to ever label her as innocent or childlike or cute—even at thirteen I knew that calling an adult woman any of those things was degrading—as that simply wasn’t what I heard or saw. Rather than the songs being funneled through, as Stephen Holden said in his New York Times review, a “preternaturally wise and loving child” with “radiant adorability,” I saw songs funneled through confidence and knowledge and ambition and anger and conflict and individuality.

I finally saw Peters perform a live concert in 2002. The concert was at Radio City Music Hall and in conjunction with the album “Bernadette Peters Loves Rodgers and Hammerstein.” It was one of two concerts I went to in high school (the other was a Cher concert), and when I got home, I devoted eight pages in my journal to chronicling everything I could remember about the night, which I said was one of the best of my life. The headline for Stephen Holden’s review was “A Princess Sings Inside a Fairytale.” I didn’t read his review at the time—I was sixteen and in the final stage of not caring what anyone else thought.

Roughly six months later, when she appeared as Mama Rose in the 2003 Broadway revival of Gypsy, I knew that people thought she had a type and Mama Rose wasn’t it. The revival was an uphill battle between the naysayers and the economic climate on Broadway. Peters got a Tony nomination, but lost the award. The revival closed earlier than expected. By that time, the trap of what other people thought of her was so firmly laid, there was no escaping. She wouldn’t appear on Broadway again until 2010, when she’d play Desiree in A Little Night Music and, once again, sing “Send in the Clowns.”

Re-watching her 1976 performance now I see no marks of childishness. For all of the number’s absurdity, it is not without sophistication. The stillness, the lack of self-consciousness, the way she never seems to ask anyone for approval. To me, then and now, this is the opposite of being a waif. I revisited a number of her older performances and practically all of them are free of those characteristics. I remember discovering Mack and Mabel as a pre-teen and loving her songs because her voice was different; it lacked the sound of trying to appeal to as many people as possible with as little offense as possible. A reviewer of the Mack and Mabel album described Peters as having “an ingenious way with words,” and she did, and continues to—her deliveries always have an element of someone who understands language from the inside out. In her concert and television performances from the 1970s and early 80s, she is at times zany and then calm and then angry, with movements that almost explode, but are incredibly precise. The comic precision is there in The Jerk. In Pennies from Heaven (not only my favorite of her films, but one of my favorites of all time) and Sunday in the Park with George, her performances are full of unexpected moments and originality. When I watch Bernadette Peters in Concert, the same DVD that lived by my TV in middle and high school, I still see so much of what I saw then: confidence, humor, drive, ability. And what I see now, that I don’t think I would have been able to name back then, is a model for a woman singing with moral authority, not by covering herself up, but by being comfortable in her own uniqueness—a leader for slightly weird girls with strong personalities who were never going to be happy pretending to be smaller than they were. She was her own remarkable person.

Of course, who Bernadette Peters actually is remains somewhat unknown. Thinking back on how hard I tried, as a pre-teen, to learn about her, I really never found out very much about who she was as a person. Her stance of not wanting to discuss her life was staunch and only increased with time and age. She didn’t want to talk about her mother; she didn’t want to talk about her relationships; she didn’t want to talk about the death of her husband, Michael Wittenberg, who she married in 1996 and who died nine years later. She would talk about the work, but only in a circumspect fashion. She put little effort into defining herself through anything other than what could be seen on stage or on screen.

I saw her in concert again in 2006 at Avery Fisher Hall, in A Little Night Music in 2010, and Follies in 2011, and it was somewhere in there that I began to feel frustrated not by the lack of revelation, but by the lack of definition. “Why don’t you tell them they need to treat you as a serious person,” I thought to myself. “Make them treat you like the accomplished person you are!” I was still young enough to think these were things individuals could control and that part of success was people listening to you.

This past summer, a number of Eve Babitz’s books on life in Hollywood were reissued. One of them was Sex and Rage, which was originally published in 1979, the same year as The Jerk, the same year Lucille Ball rolled her eyes, and the same year Peters was doing concerts where her performances could bounce back and forth between extreme stillness and an almost violent energy. In Sex and Rage, the protagonist, an it-girl named Jacaranda, refers to the fabulous in-crowd as “the barge,” and in one of the novel’s most famous passages, reflects that girls like her, the young and cute, “the ones who were brought aboard to amuse the barge,” disappeared through the only two acceptable ways out: dying young or being forced out by an STD. Any other means of escape, through self-invention or self-actualization, are not permitted—it’s the one thing that truly upsets the barge. And maybe this is something Bernadette Peters learned early: how people put women in a box and want them to stay there, and act the way that type of woman is supposed to act and look the way that type of woman is supposed to look and say the things that type of woman is supposed to say. And people have never liked it when women break out of those boxes and break the rules that have been set up for them, because it forces people change the stories they’ve been telling not only about those individual women, but the stories they tell about themselves.

Peters can act, she can sing, she can dance. She can deliver comedy and drama. Her hair was always too big, her skin too pale, and her body too small and too big at the same time. Bernadette Peters is never not going to take up space. She vibrates with uniqueness. And perhaps it was her uniqueness that made her so hard to capture. In lack of any accurate language, and out of fear of any woman who refuses to remain one easily definable thing, people tried to contain the complexity and contradictions of her performances and her person by labeling them that of a precocious child, as young and cute forever.

Bernadette Peters will be 70 this week. She is currently starring in Amazon’s Mozart in the Jungle, where she plays the President of the fictional New York Symphony, and once again on Broadway in Hello, Dolly!. I saw Hello, Dolly! a few weeks ago, and when it got to the end of the title song, everyone was on their feet clapping. When I sat back down I felt a strange mixture of both being very happy and very sad. Because, beyond everyone standing for the performance, and everyone standing for Peters, I also think they were standing for something else, something that was maybe labeled “young” and “innocent” instead of another word: hope. Maybe it was hope that people saw time and time again when they watched Bernadette Peters perform. Not hope that her characters or songs would have a happy ending, but hope that being unique and being your own person could win out in the end; that you could be many things at once; that you could always hang onto all the things that made you you. When asked to give advice to young performers, Peters always answers with, “You’ve got to be yourself.” It is the easiest thing, and so often as we get older—as it is the best and worst of times, as it is the beginning of the end and the beginning of a new beginning, as you jump off the barge or get pushed off of it—it is the hardest thing. But maybe there is still hope that as the dancing men’s canes turn into the bars of a jail cell, that you too can keep your head up and your shoulders back and look through the bars as your own remarkable person.