On Adam Guettel, Silence, and the Fear of Nothingness

September 24th, 2018

Recently, I saw a play that was excellent and that I hope everyone buys a ticket to see. And I’d tell you the name of it, except I looked at the Playbill and saw that someone who had worked on the show was a teacher I had my freshman year of college who was extremely emotionally abusive, sexist, and inappropriate. It wasn’t sexual, just to be clear. I don’t know what caused it. Maybe he just hated me? Maybe he didn’t even give me all that much thought and I was just a diversion? I don’t know. What I do know is that by winter break of my freshman year, I was unrecognizable to myself. I mean, I really destroyed myself—physically, mentally—and I found myself unable to do anything to help myself, including the thing I most needed to do, which was leave the school. Even now, I can’t really explain what happened. I was—and am—an upper-middle class white woman who had resources, had always been outspoken and opinionated and funny and, if not always confident, believed deeply in my own destiny for greatness; I identified with the white men on Aaron Sorkin television programs. And nothing that happened was trauma, not in the sense of the word as I knew it. By that time I’d experienced both sexual and violent trauma (those ships had sailed before I had my driver’s license) and I had gotten through those things with my sense of self and my goals in tact. But in college I did not. And what I was left with was the blurry static of cruelty, shrugged off or seen as adorable or artistic by the other faculty members, and my own inability to explain the significance of what happened to me in school that year and how the effects radiate outward to this day.

This isn’t something I normally talk about. In fact, it’s something I talk about next to never. Because I’m afraid of people thinking I’m crazy? Bitter? Whiney? Because, in the words of Jennifer Aniston about her mother, “You can’t blame other people for your issues forever?” Well, I’ve come to see crazy, more often than not, as a compliment; yes, I am still bitter, if you want to know the truth; I try and save my whining for any and all menial or physical tasks; and in my early twenties I used to order dirty martinis because I’d read that’s what Jennifer Aniston drank, which, actually, strikes me as one of the only things I did in that period that was organic to my personality. I think the real reason I seldom talk about it is because it’s hard to explain and I worry that I’ll be met with indifference or a shrug, and I’ll be left knowing that someone else knows and it made no difference to them. After all, in a way, nothing really happened, I guess. Sometimes it’s really hard to tell the difference between things that mean nothing and things that mean something.

Roughly a decade ago, I was at a fancy benefit lunch for a theatre company where the theme was Stephen Sondheim. Throughout the lunch, people—mostly men, as I recall—kept getting up to talk about Sondheim’s influence on their work. A running joke became there will never be another Stephen Sondheim—except maybe Adam Guettel. Guettel is the son of Mary Rodgers and grandson of Richard Rodgers. In 2005, he won the Tony Award for Best Score for The Light in the Piazza. And on the morning of Wednesday the 19th, he took to Twitter to tell people that he thought Supreme Court nominee Brett Kavanaugh was qualified and that the accusations of sexual assault against him lacked credibility. Later that night, he came back to Twitter to double-down on his position. If you are a person who reads The Interval, I am going to assume you are a person who already knows why that position is sexist, and if you are a person who just happened to stumble on this piece, make it this far, and thinks, “I agree with Adam!” then I’m going to assume you’ll be closing this browser tab right about now and wishing it was paid content so you could demand a refund. So, let’s all start from the knowledge that his opinions are wrong, unwarranted, and sexist, and not legitimize them by having a debate. Of course, he has the right to express his opinions, but people also have the right to say that his opinions are sexist, and I would have hoped people would have felt a moral urgency to do so, for prominent members of the theatre community to make clear that they will support a workplace that values women, that they believe in equal protection, that no means no.

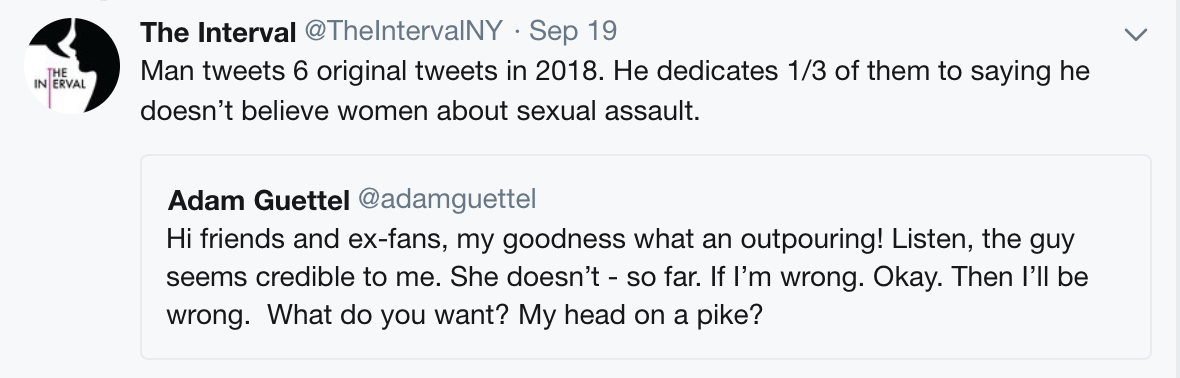

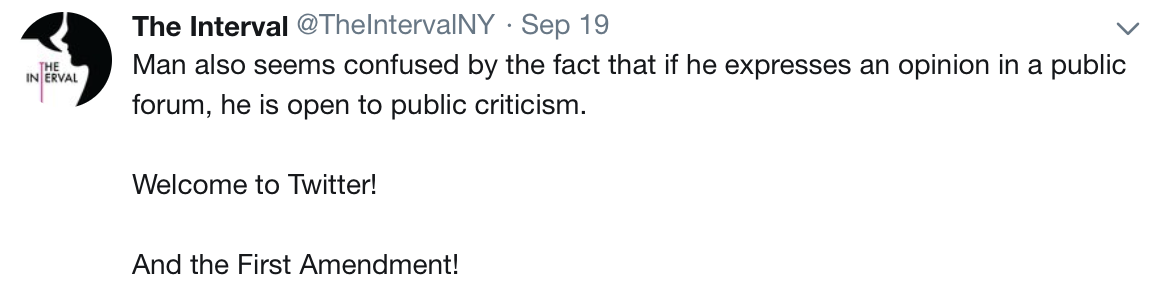

Until Wednesday, I didn’t even know that Adam Guettel had a Twitter account, that’s how seldom he has used it. Currently, in 2018, Guettel has posted six original tweets. Now, one-third of his tweets are devoted to saying he believes a woman lied about sexual assault. I saw his tweets on Wednesday afternoon, and retweeted them to The Interval account with comment. You can see them below. I was the one doing social media that day, took screenshots of the tweets, and put them on The Interval’s Instagram story.

I wanted people to see them. I wanted people to know what he thought. I wanted people to be angered by it. In the last four years, I’ve come to notice a pervasive obfuscation that happens in the theatre community where people make a choice to not notice things, to not ask questions. The less someone knows, the easier it is for them to maintain an air of plausible deniability and play both sides of the fence. In a way, this is pragmatic in an industry that is small and functions so much on personal relationships. The easiest way to never alienate anyone is to never stand up for anyone, and the easiest way to assuage a conscience has always been to say, “I didn’t know.” I find that exhausting and untenable, and I wanted people to not be able to say, “I didn’t know.” He put it on the internet: he wanted people to know too.

My guess is, by now, a lot of people have seen his tweets. Still no prominent members of the theatre community have spoken about it. I think they should. Much in the same way that it’s not okay to sit at a dinner party and hear someone tell a sexist or racist joke and not say anything, but later pride yourself on not laughing, it is long past time for the theatre community to look at what type of community it truly is and for individuals with a platform to speak up and no longer tacitly condone behavior and views that create a workplace where women are not valued. This responsibility should not be disproportionately laid at the feet of women, who, in general, have less job security in the theatre to begin with. It’s up to everyone.

And the thing with the Guettel tweets is that it should have been easy. He made his views clear. He felt so strongly about his opinions that he decided to share them publicly for everyone to read. There is no gray area here. There is no “he said, she said.” It’s not complicated. I have seen prominent theatre professionals use social media to condemn cell phones and anonymous strangers for less. The Interval, which as a journalistic publication is 100% fair game for public criticism, has had prominent theatre professionals tweet to tell the world that they did not approve of the following things we had on our Twitter: a.) A typo in a tweet that we’d apologized for b.) Giving Jeanine Tesori too much credit c.) A joke pointing out that during awards season women are seldom allowed to talk about their work or accomplishments and instead must spend all of their time talking about being a woman. Because it is my job, I have wondered why it is that people felt so free with us and have been so silent about him. Is it because we are seen as being that much less powerful? Less important? Because I am a person with some self-worth, it makes me angry. And because I am an adult person with financial stability, it also makes me wonder what it must be like to be a young woman watching people they admire stay so silent about Guettel’s blatant and public sexism, when it would be so easy to condemn it. What is she being told about her worth and value to this industry, before she has even had a chance to establish either on her own terms?

Of course, it is easy to sit at a distance and tell people what they should do. And it’s easy to condemn people who are at a distance; people who you won’t run into at a party, won’t audition for, won’t work with—to only ever talk about things in general and not the specific individuals. The theatre community is small and everyone is afraid of never working again. But what if people decided to start treating the boogeyman of, “This is how it is and this is why it’s scary,” exactly as that? Something made up of our collective imaginations that can begin to be undone by saying, “That comment isn’t okay, that behavior is unacceptable, and I will not sit here and pretend I didn’t hear it. Treating women badly doesn’t make you cool and it doesn’t make you artistic.” Not for the sake of men like Adam Guettel, but for the young people watching and for the people who have stories that are complicated and hard to explain or stories that are criminal and difficult to tell, and for the people who are left wondering, “If people couldn’t say something when it’s easy, will they ever say something when it’s hard?”

The few times when I have publicly spoken out about something it has not been scary for fear of what might happen to The Interval. The Interval could disappear tomorrow and I would be fine. What has been scary is that old fear of the shrug of indifference; the thought of silence, of the possibility that I might be standing by myself; that people who I respected will go on as if nothing had happened—and then I don’t think I would be fine. That strikes me as terribly difficult, and, in that, I don’t think I am alone. I wonder if some of those very same women I respect so deeply have sat alone at night filled with the same fears. I am almost certain they have.

There’s that quote from Mr. Rogers that people always post on social media whenever something bad happens—that one about how his mother told him when bad things happen, to look for the helpers. Adults are always posting it on social media, usually for an audience of adults. I always think, “If everyone is so busy looking for the helpers, who is actually doing the helping?” It’s time to help make it easier for people to speak out and feel like they will be heard and supported. It may not be seismic change for the industry, but it is definitely not nothing.