Costume Design x3: Catherine Zuber, Emily Rebholz, and Kaye Voyce

Written by Victoria Myers

April 25th, 2019

Costumes are important. Costumes help tell a story, locate the play for an audience, and help the actors to develop characters. The costume design field can vary widely in process from designing costumes that will be built from scratch to scavenging through vintage stores to find the perfect item, all while having to adapt to projects of varying budgets and scopes. It is also a field that has historically been dominated by women. This spring, Lincoln Center Theater had female costume designers in all three of their spaces: multiple Tony winner Catherine Zuber designed the costumes for My Fair Lady in the Beaumont, Emily Rebholz for Nantucket Sleigh Ride in the Newhouse, and Kaye Voyce for Marys Seacole in the Claire Tow. I recently spoke with all three about how they got into costume design, working in different spaces, if they feel the field has been undervalued, and more.

Emily Rebholz

How did you get interested in costume design?

I’ve always loved clothes and I was always sort of involved in theatre. When I was a little girl, I would do community theatre. I was always involved in theatre and I always loved clothes and we moved around a lot when I was growing up. I would always try out for plays wherever I was living. By the time I got to high school, I was living in Memphis and I stopped getting cast in all the plays; I was not a good actress. I’ve also always been a huge reader and knew that I really wanted to be involved in telling stories and all of that. So I asked the drama teacher if I could help with the costumes since I wasn’t cast in the show. And she was like, “Of course,” because she was the teacher that did every single thing. I just started doing it when I was really young. Then I went to Northwestern for undergrad, which has a big theatre program. I was not in the theatre school. I thought I wanted to be a lawyer, but I wanted to take a lot of the electives and it was really hard to get into the costume design class because it was one of the ones that the theatre majors had to take. I took some sort of roundabout history of fashion and I met one of the professors, and she got me into costume design and because Northwestern has a Grad program, they allowed me to take a lot of the Grad school classes while I was an undergrad.

I just love doing it. I designed costumes at Northwestern and took a lot of the classes. At the same time, I had an English degree and I still thought I was going to be a lawyer. And then somewhere along the line I realized that [costume design] really was a career. I was really lucky to be mentored by my professor, Linda Roethke. I had to learn how to draw. I was always very studious and I didn’t know how to draw, so she literally taught me how to draw. They guided like, “Okay, we think that your next step should be to move to New York.”

So I moved to New York. My boyfriend was already living here at the time. He was in medical school and I went to the Art Students League to really learn how to draw for two years and worked at a restaurant and went to intern at Williamstown [Theatre Festival] and then I went to Yale, and that just kind of took off. It was a really organic process. Because I love stories, I’ve made the analogy that we all speak different languages, and I honed in on speaking the language of clothes. The way they communicate and tell a story. I’ve always been interested in it.

What do you think is the biggest misconception people have about costume design or a career as a costume designer?

People always think it’s a lot more glamorous than it is. It’s not. I assisted a designer when I first graduated from school. We were at the old Signature Theatre and it was like midnight and we were on the floor painting clothes and distressing. I feel like it was like the best advice I ever was given was when she was like, “You know, I’ve designed on Broadway. I designed at the Met. It doesn’t matter what you do or where you’ve been, you will always end up on a dirty floor at midnight painting shoes.” And it’s so true. It’s a lot of work. I think there’s a misconception that a lot of it is the drawing or the making. The sketch is 10% of the design. So much of it is the research, and the knowledge, and then the fitting and translating. And then the carrying the bags and the schlepping and working with a million different people and opinions. I love my job, but it’s a lot of work.

How do you find that working in different spaces, different sized theatres, and different budgets affects your job?

The biggest things that affects it is support. The more support you have, the more enjoyable the process. And I think that that’s one of the things that’s affected the most by budgets and different size—not the actual physical theatre, but the budgets. Support is really key, and good support is really key. When you’re starting out and when you’re doing smaller shows, you’re doing everything yourself. That makes a huge difference. It’s not even the budget of the materials. I designed two shows at Santa Fe Opera and their costume shop is made up of about 75 people. My materials budget might be the same as something in New York, but where that money goes when you have 75 people working to make your designs come to life is like a whole other thing.

You’ve done a lot of contemporary shows that are set in the present. Are there any particular challenges in doing the costume design for that?

I think it’s deceptively sometimes harder. Especially with a new piece, you’re working with actors that are creating the piece, and the writers that are creating, and everyone’s coming together to make it. And I think that with contemporary clothes, everybody’s got an opinion. Everybody has an opinion and there’s a real understanding of what’s going on. [Whereas] you dress someone in design that’s from the 1700s and they have no clue and it’s like, “Okay, we’re building this, you’re wearing it. We’ll figure out how you can move in it and work in it.” You always have to make adjustments. Always, no matter what period, you have to make the actor feel comfortable. But with contemporary clothing, you want it to be there but you want it to recede. You don’t want it to be the thing that you’re looking at the most. You want to tell a story with it, but you don’t want it to be so obvious a lot of times.

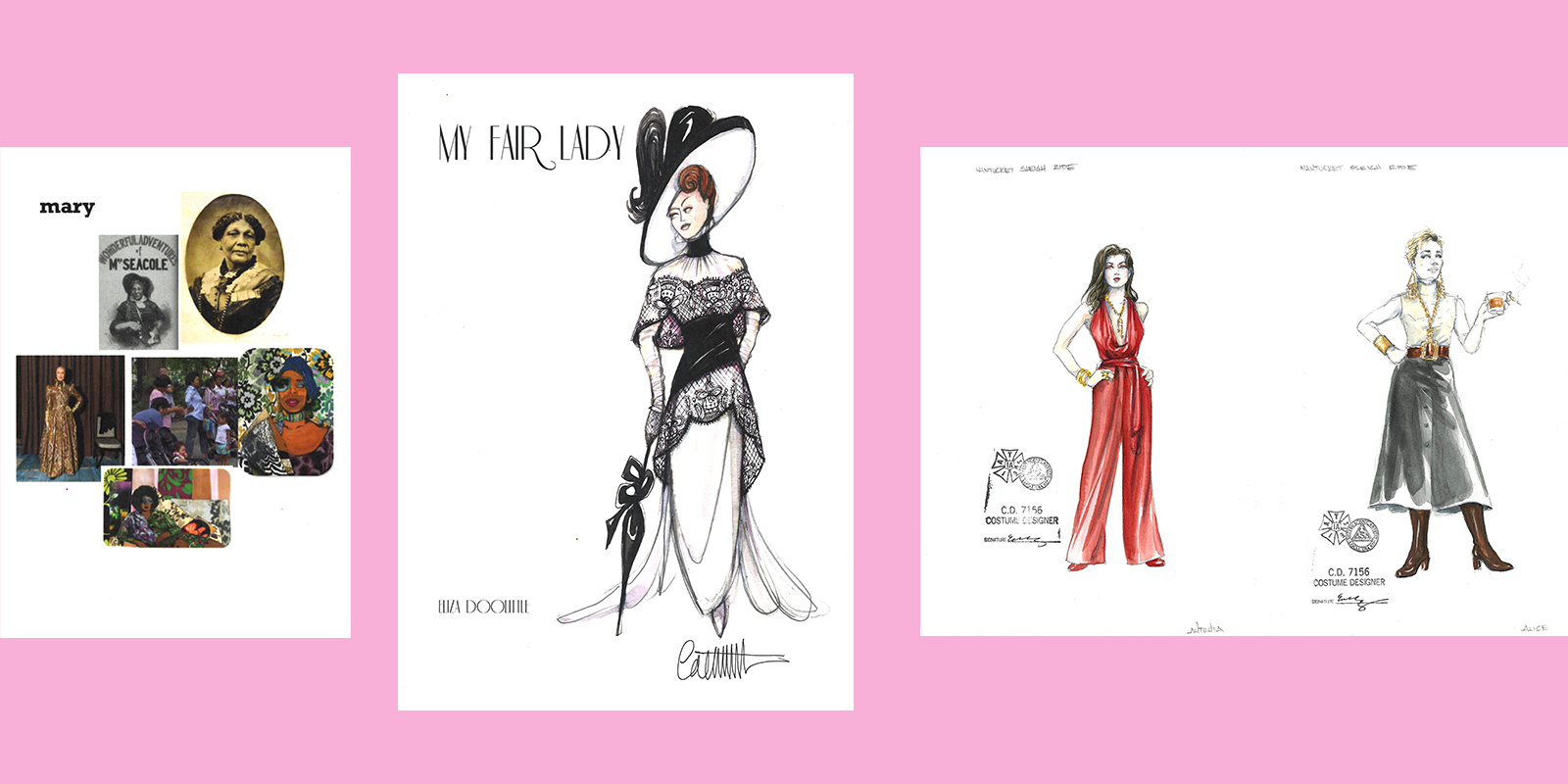

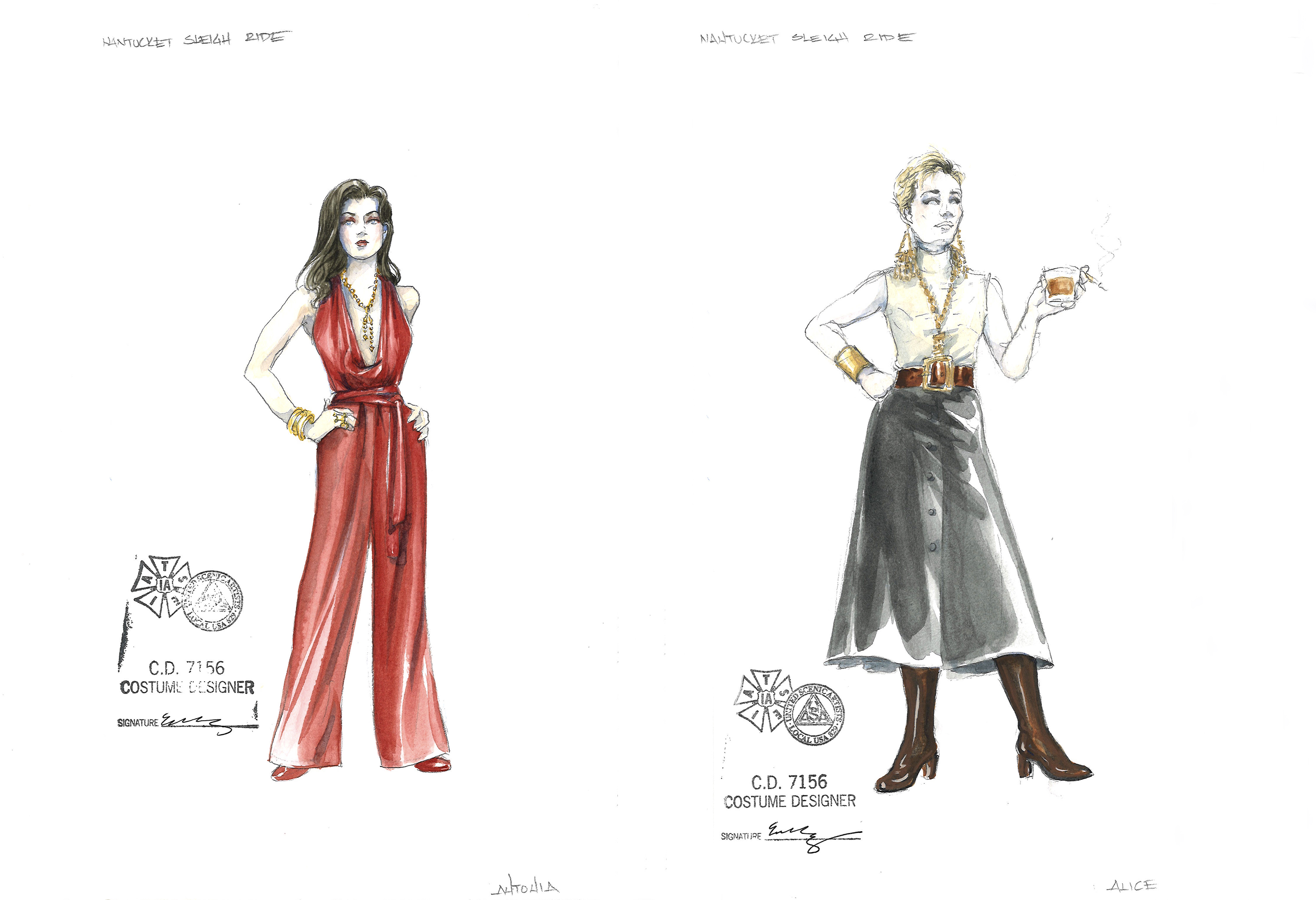

For Nantucket Sleigh Ride is there a particular costume that you really like that you could take me through where the idea came from and its execution?

It is mostly set in 1975, and working with Jerry Zaks was really wonderful, and the process of designing was wonderful. It was really nice to have sort of a contemporary feel to it because even though it is mostly in 1975, Jerry and I really wanted to make sure that it was accessible, and when the story’s kind of zany, you need the people to feel somewhat relatable. What was wonderful about this was it really was all completely sketched out. Oftentimes with modern dress, I don’t sketch out. I do mood boards and collages because I know that I’m going to need to have so much flexibility in the fitting room.

It’s vintage, which is really fun for me. It was really fun to do the women’s clothing, like Tina Benko, who plays Antonia and then also plays Alice. She talks about tango, and so for Antonia, and I really wanted to have a sensuality with the character. I was looking through tons of different 70s research and looking at Bianca Jagger and Halston, and all these things in the 70s. These awesome jumpsuits kept coming up and I’m like, “Well that would be really wonderful because it’s something that’s really stylish right now and was really stylish in the 70s.” And also feels like something she could be wearing at home, but it was a little bit elevated. She’s at home, at her house, getting ready to travel, and who’s really sitting around in a red silk jumpsuit? But it isn’t a tango dress, which was my first iteration and then Jerry was like, “Well, she is at home.” So we went into this world of Halston and sensual. The silk feels sexy and gorgeous, but also is relatable to today. Then what was really fun is then she flips and plays Alice, who is a magazine editor in New York City and a little scrappier. John Guare had been thinking of Edie Sedgwick. I looked at a lot of Edie Sedgwick research. The thing about Edie is a lot of it is from the 60s and it’s not quite the 70s, but I took that vibe and every time you see Edie, she’s got these huge fabulous earrings on, and this wonderful blonde cropped short hair. I went to a new vintage store that I didn’t know about up in Yonkers, and found this amazing vintage jewelry, and kind of based the outfit around that. It’s fun to get to do both.

I read an article in Variety that had to do with costume designers in film and TV. And they were saying that they felt the field had been historically undervalued because it’s made up of a lot of women. I was wondering if you felt that was true for theatre as well?

Sometimes I do. “It’s just clothes, right?” I feel like that is a phrase that you hear and you’re like, “Well, it’s not just clothes, it’s telling a story.” It’s a lot of work. It’s making sure what I put on the paper works with the actor. It’s making sure that it works with the story. It is a long process and I think that is part of it. It’s not a set design where you build a model, and then a shop builds it, and then you put it on stage, and tweak it. You’re constantly tweaking and working with others and morphing your thoughts. I think it’s very subconscious but, yes. I think it’s there. I mean very, very often the only woman in the room on a design team is the costume designer.

Kaye Voyce

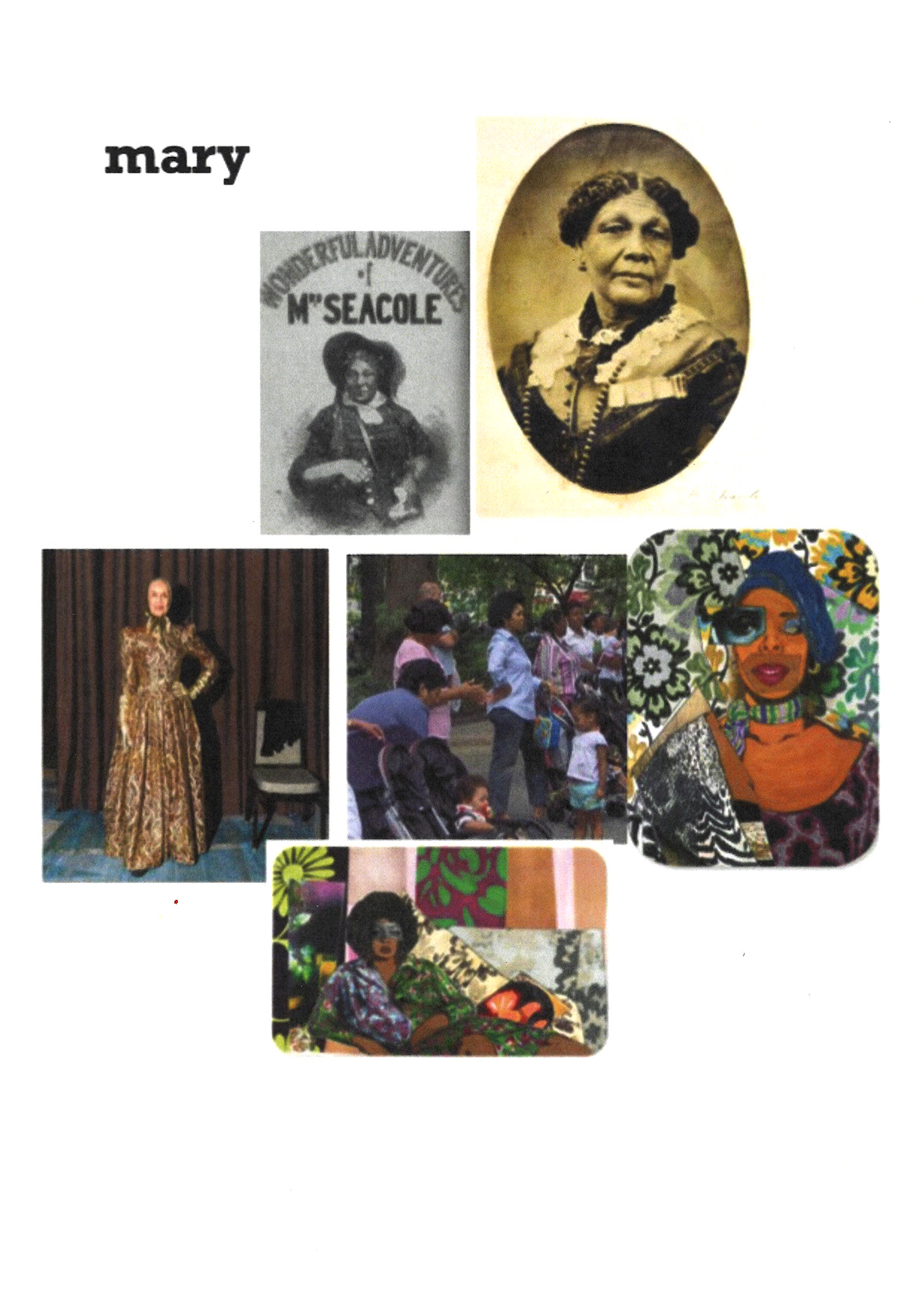

For Marys Seacole, what was your process?

I started researching the play before we had the final draft. The text was changing the whole time, so really it was doing the research about the real people, about the contemporary overlap, trying to figure out where it might go. The process was totally organic during rehearsal. The design was very, very loose until we were in rehearsal, and it was really just about dealing with real objects, real people, trying to figure out the track and how it moved. It was really an in-the-moment process.

What were the technical challenges, especially because you have people playing multiple characters in different time periods?

A big part of the design process actually is really just figuring out how people change from scene to scene, and keeping on top of the text changes and timing changes, and figuring out who was doing what when. Basically as a costumer, you also have a chart or a grid going of who’s in what scene when, and what kind of time you have. It was staying on top of that every day with stage management, and figuring out the most efficient ways of dealing with people changing clothes. Also technically, since we had a low budget and a limited wardrobe staff to actually help with the changes, figuring out what could happen when and where. So, the technical part of it was actually a huge part of the design.

How did being in a smaller space affect your process? Did the audience being close to the performers present any challenges?

The distance didn’t really have anything to do with it. It was more knowing that we wouldn’t be able to build anything. That was the biggest thing that our budget indicated, was that nothing could be built, which in a historical show means that you will be limited to what you find. And also knowing that the text was going to be changing and developing as we went, so not wanting to commit too many resources to anything too quickly became very important. We pulled some things from stock. We pulled things from the TDF costume collection, just to give ourselves the flexibility to go spend money later on when things were more solidified and we had less time.

The costume collection is a resource for non-profit theatres in New York and all over the country. We were lucky because Lincoln Center Theater has donated costumes to it, so there’s some kind of credit. Essentially we were able to borrow things for the cost of dry cleaning. So, we got a couple things from there. Most of the Civil War garments are from the Lincoln Center Theater stock.

When you’re doing a show, what’s the balance between thinking about how all of the pieces go together vs. thinking about individual pieces?

I’m always trying to think of the big idea and the big wish. For me, my work is much more making the event than making clothes. The overall event of coming to see this play and what you get out of it, to me, is much more interesting.

How did you get into costume design?

I thought I was going to be an artist. I moved to New York City with the thought of going to college and then eventually going to art school. My first year here, I fell in with a bunch of filmmakers, performance artists, drag queens, people in bands, and did essentially environments in costumes for the work that those people were doing, without realizing that it was something that people did. Finally someone told me, “Oh you can do this. It’s possible.” I ended up transferring into the design program at NYU as an undergrad, doing a five year combined BFA/MFA program that they don’t offer anymore, with no theatre background, with just a fine art background. It ended up being a great thing. It was just a mix of everything I enjoyed, the art history aspect of it, the psychology aspect of it, the fact that it was collaborative, the social history aspect. It’s a weird thing of having to become an instant expert on something in every project, you’re always working on something different.

What do you see as being the biggest challenge about a career as a costume designer?

I think that the biggest challenge in New York City is the lack of institutional support. In other fields—set design, lighting design—theatres tend to have an infrastructure to support those departments. The technical director is a master electrician. And for a myriad of reasons through the years, that position exists less in costumes. As a lot of shows in New York City are shopped in the contemporary way, it ended up taking on a very on-the-ground, do it yourself-er event, which can be great. It’s just a different process. I’m taking on a lot more responsibility for how things get done, and for budgeting and things like that, in a way that other departments don’t necessarily [have to].

I read an article where costume designers in film and TV were talking about how they felt that the field was undervalued because, historically, it had been a field that had a lot of women in it. Do you feel like that’s true with theatre as well?

Yes, I do. I do feel like because it’s traditionally considered women’s work to deal with clothing, we’ve definitely been undervalued. I also think that it’s been undervalued by institutions, which have been traditionally run by men. I think the women doing the work have, because of society, undervalued themselves. I think that’s something that people are trying to change now. Trying to change the system, but it’s hard and it takes time. It takes relearning how you do your job and what you fight for.

Catherine Zuber

How did you get into costume design?

I was a photographer, initially. I really enjoyed taking photographs and appreciating the photographs of others that had to do with setting up scenarios and looking at interesting physical spaces, and if there were people, how those people fit into those spaces, and based on what they were wearing, creating a fantasy image of a false reality. I always collected vintage clothing that I used to wear myself when I was in my twenties. I moved to New Haven with a boyfriend who was going to the photography program at the Yale School of Art and Architecture, and while I was in New Haven, I got involved in the theatre scene that was going on there at the time. I applied to the drama school at Yale University, and I got in, and I started my career at Yale. That was in 1981.

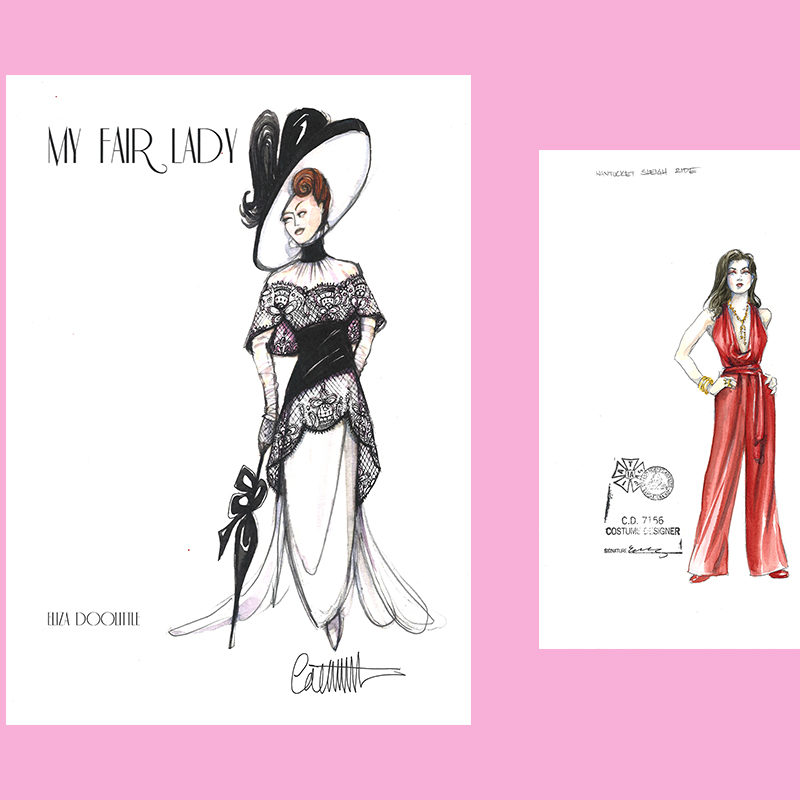

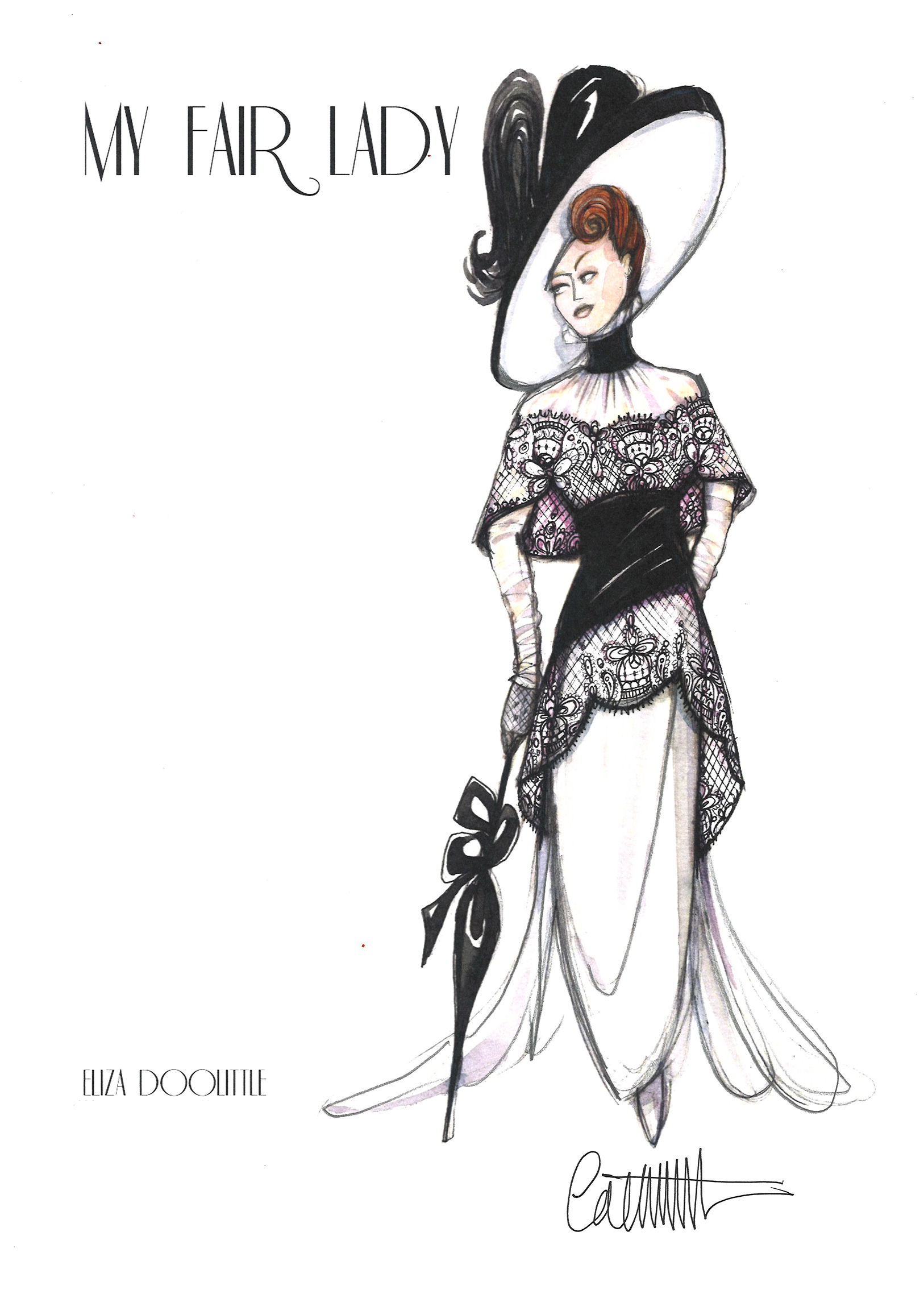

When you get a project like My Fair Lady, how do you start thinking about it? How do you work with your collaborators? What type of research do you do?

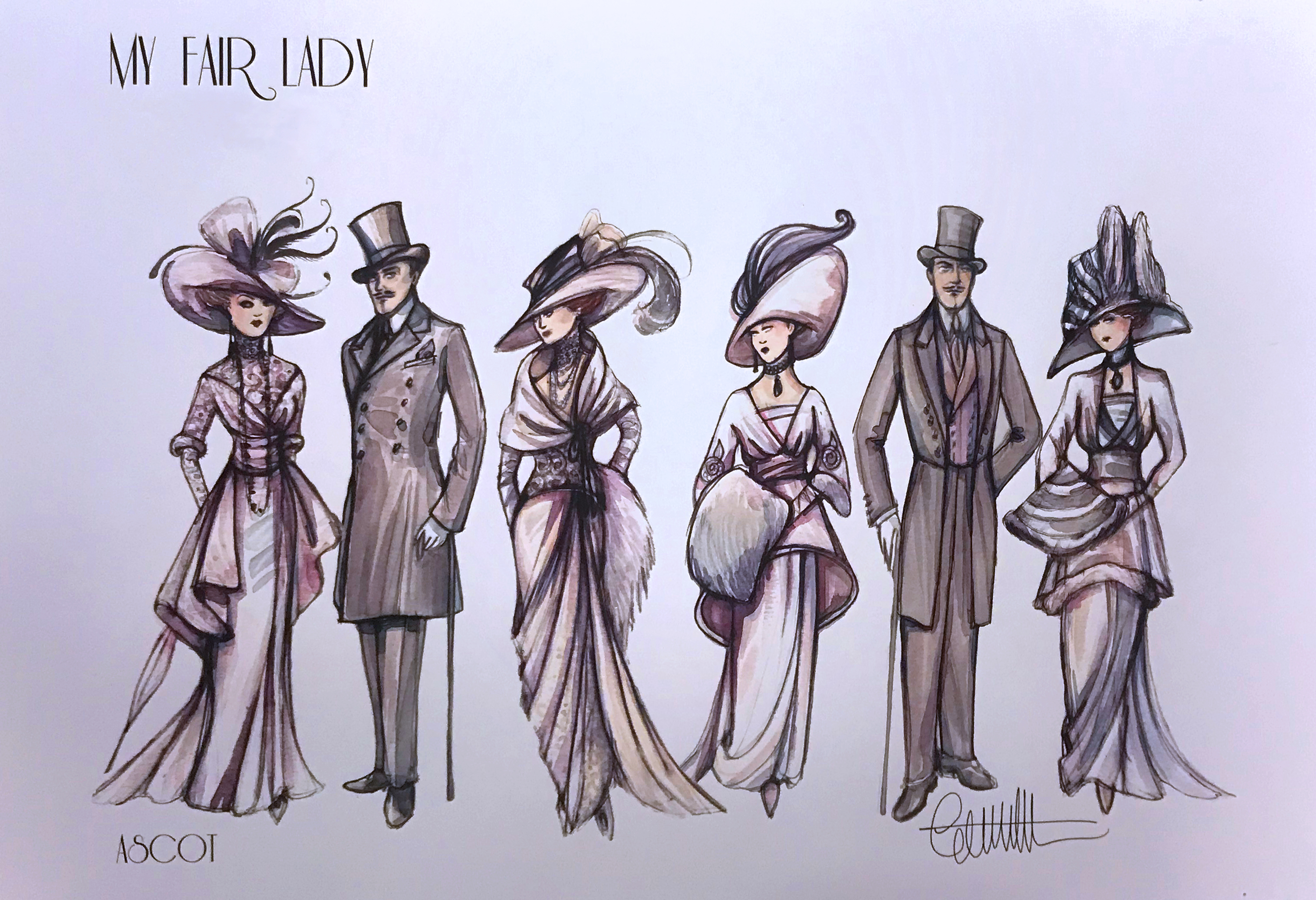

The first thing we do is we talk about what we want to say with the piece and how it relates to a modern audience. What are the things that we want to embellish? What is the story we want to tell? And then, after we all meet together on that, we each go our separate ways. Within each of our disciplines, we pursue research, and research for me can entail photographs, paintings, fashion, illustrations of the time period. Particularly with My Fair Lady, there were so many wonderful photographs of the late-Edwardian period that we could tap into. Also, studying the class differences. What is the hierarchy of the world we’re creating? What do the working class people look like? What do the aristocrats look like? What does the serving class look like? There are so many different levels. We set up the hierarchy of all the different classes of people and then studied the piece to see what situations they’re in that pertain to My Fair Lady.

The opening scene is a wonderful illustration of a lot of different classes of people being in the same place at the same time. You have the very aristocratic opera-goers leaving Covent Garden Opera. You have vendors selling things. You have flower girls, of which Eliza is one. You have prostitutes, you have ne’er-do-wells, you have people that are up early because they have to tend to a business where they have to start quite early in the morning. The first scene is a wonderful collection of all those different classes. Then, as you move through the piece, it splits off into different scenes, where you go to Higgins’ home, and you have the serving class. You have what the home is like of someone who is from the ruling class. That’s a big part of the My Fair Lady story, so it was very important that we really visually captured those contrasts.

Are there any specific challenges when you’re dealing with a musical where there’s a large ensemble and making sure that everyone is cohesive, but also different?

Within an ensemble on any musical, you can have a performer have to do all those types of people. It’s not like they’re assigned one role, and that’s it. So, our ensemble, they are working class, and then in the next scene they could be an aristocrat, and then the next scene they’re a drunk stumbling out of a bar. And that has to happen within seconds, in terms of a quick change. With each actor, we tap into their wonderful skills as actors, with body language and dialect, to become those different characters, but also with costume. In a musical like My Fair Lady there are lots of quick changes. They not only have to become the person, but do it quite quickly from scene to scene.

With My Fair Lady, because there is a movie that has very iconic costumes, did that present any particular challenges to you?

It’s a very beloved film and beautifully designed, but André Bishop, our artistic director, really didn’t want to copy the movie. They visually wanted to make sure that we had our own voice. For instance, with the Ascot, I thought it would be more interesting to pay homage to the movie, where Eliza has the black and white elements, but the rest of the ensemble were in mauves, and violets, and pale grays, and very transparent and fluid fabrics. And except for the principals, they all have white hair and these very large hats that are all very translucent and very ethereal, and we could pull the men into the palette as well.

It’s not like a movie where you can have quite a few extras with an unlimited cast. In a musical you have to come up with ideas sometimes to make crowd scenes seem a little more populated. It just seemed if men were in that palette as well, it would help create a more visual solidity that Eliza can react against—that there really is this cohesive aristocratic population that she’s trying to fit into. With the two Elizas we’ve had, Lauren Ambrose and Laura Benanti, they both, in their own way, were quite brilliant at turning that unease and that observing who these people are into very comic body language moments. So, the fact that Eliza was in black and white and set apart from everyone else was a plus.

What are some of the other technical challenges with a musical?

When you’re doing a musical, it’s in a very specific time period, and there’s choreography. You have to honor the time period, but also, the costume needs to move, and look appropriate, and match the choreography, whatever that may be in any musical. In our musical, My Fair Lady, it was waltzing, and we’re right before World War I. We’re in 1913, and the silhouette is not the most waltz-friendly cut. But by having these elongated elements that pull away from the costume and then are held on the fingertips of the actors, it gave quite a lovely movement, and the dancers are so talented, and our choreographer Chris Gattelli did such a beautiful job with it all. It really was a collaboration, trying to master the combination of those two concerns.

The Beaumont is a fairly big theatre. What considerations are there for how you create something that looks the same from the front row as the back row?

In theatre you always have to think about head to toe. Everybody is seeing the full figure all the time. That means that the hair, hats, shoes, everything needs to be taken into consideration. Whereas, I think in film, where you can do a close up, it’s more important what’s around the face, and usually from the waist up. Not that the whole full figure isn’t important, but in theatre, every element has to be accurate, and it creates a silhouette. In terms of up close and far away, you do have to sometimes heighten the reality a little bit. Sometimes, if it was too realistic from a distance, it could just not be as in focus, so there are, maybe, color choices and making sure that the silhouette is sharp. Making sure that it’s quite clear, from close up and at a distance, that it reads effectively. I do a lot of opera at the Met, and it’s quite the unique challenge in that the Met is such a large house. Then, usually into the run, they’ll have an HD presentation that goes live worldwide, and it really is like a film, so you do have to think about those two elements and serve both demands.

What do you see as being the most challenging part of a career as a costume designer?

I think one of the most challenging things is making sure that the actor feels that you’re helping them become the character. For instance, using My Fair Lady as an example, the character of Eliza goes through quite a journey, not only emotionally, but it is reflected in her clothing. The Henry Higgins character also goes through quite an emotional journey, but he is still consistently in the same class. Whereas, Eliza starts out as a flower girl, becomes someone that is in the hands of men that dress her, then becomes her own person. It’s quite a wonderful journey, and it was really exciting to have the challenge of making sure that their clothing reflects that and helps them feel like they were telling the story appropriately during the arc of the storytelling.

Over the course of your career, what changes have you seen in the industry that you feel affect the costume design field?

For me, the biggest change is the use of LED lights. I think it has completely changed how color can be perceived on stage. It has become a challenge. We spend so much time sourcing the right colors for certain things, and it has meant that we have to be a lot more careful about types of fabric, the way that they pick up light, the way they’re perceived in light, and we’ve had to do a lot more painting of fabric to give it shape. The new technology in lighting is starting to become a little more sophisticated in that there’s more variance within this new technology, but I have noticed a big difference. Even with wigs, the way that hair color is perceived with LED lights. Things can go quite dark, and then you look at the wig up close, and it’s a really beautiful rich brown, and then you go onstage, and it looks almost black. Just things like that are a bit of a challenge, in terms of recent developments.

Is there anything relating to budgets that you feel has changed over the last couple of decades?

Some projects have very fair budgets. Other projects, just by nature of where they’re being done, you know going into it that it’s going to be a low budget, and you just have to tailor your approach to where you’re working. Of course, doing a project like My Fair Lady, it’s wonderful to have a decent budget for a project like that. But Lincoln Center is very cautious. They’re careful not to overspend on anything, and they’re quite watchful; we have to really present in very careful detail how we’re spending our money.

I think that the thing that most costume designers feel right now is the fabric stores are closing down, which means that there are fewer options. It’s harder to source fabrics than it was, let’s say, five years ago. And the costume shops, the real estate is quite high, so when you have costume shops made, the prices are higher than they used to be, and most of that is just because of real estate issues. Some shops have to move out of town, which makes the logistics of having costume fittings and having the costumes made more of a challenge. But we just roll with the punches and do our best within the budget we’re given.

I read an article about costume designers in film and TV where they were talking about how they felt that the field had been historically undervalued because it was considered a female field.

I totally agree with that. That’s absolutely true. I don’t want get into specifics, but I absolutely agree with that. So many times they feel the set designer and the lighting designer are more important, and then the costume designer is an afterthought a lot of the time. It gets a little exhausting sometimes, trying to change people’s point of view on that. A lot of people do value costumes quite highly, so this isn’t across board, but it definitely, definitely is undervalued. I’m totally on board with that observation.